IMPORTANT NOTE: For this section, I will refer to many New York Times articles, which are reviewed in the below accordion; more extensive info about how articles are documented is given there. Note that each article has a unique "IDdate" which I use to cite them, based on the date the article was completed (as opposed to when it was published; although the publication date is used when no writing date is given). This is given as year_month_day, where days 0-9 have a leading 0 (but not months). For example, an article finished on February 8th, 1958 would be IDdate’d 1958_2_08. If there are two or more articles written on the same date, a letter ("a,b,c...") is appended at the end; if the article was the first documented, it would be IDdate’d 1958_2_08_a, and would be cited in text with an asterisk (click/hover over with cursor, or click on mobile), like so: *(1958_2_08_a).

IMPORTANT NOTE! SIDE BUTTONS

On the side, the "↑" (up-arrow, ie ⇑) button brings you to the top of the page. "🍏📗TC" shows the table of contents. "📘GD" gives the definition of genocide per the United Nations Genocide Convention (1948) - that is, the legally enforceable definition. "❓🔴GL" gives a glossary of terms used throughout the article. "⚫⬛AC" gives various acronyms used in the article. "⚪⬜DR" gives a figure with crude death rates (CDR) per thousand people (‰) over the past 160 odd years for several countries. "📚🔖BL" gives the bibliography.

Caption: Aerial view of Angkor Wat ("City/Capital of Temples"). The temple complex was built in the 12th century CE in the capital of the Khmer Empire, then known as Yaśodharapura, and today named Angkor; by the latter name the Khmer Rouge also referred to the Khmer Empire. "Lost" to the jungle, it was re-discovered by the French in 1860. (source: Britannica, link to picture file)

From 1975 to early 1979, around 2m died in Cambodia due to Khmer Rouge policies. But despite the widely held label, perhaps excepting the fate of 20k Vietnamese (and possibly, though less certainly, the Cham and Sino-Khmer), this was not genocide.

E.Introduction

The Khmer Rouge (KR) era of Cambodia (then known as "Democratic Kampuchea"), followed by the Vietnam-installed "People’s Republic of Kambuchea" (PRK), is, to say the least, complex. For one, the Khmer Rouge - as they are today widely referred to - were extremely secretive; to most Cambodians, they were simply Angkar ("The Organization"), and only at the upper echelons were they known as the "Communist Party of Kampuchea" (CPK), except from fall 1977 (when, internally, furtive references to a communist party began) to 1981 (when the party was officially dissolved; Angkar, of course, remained). In fact, 'Khmer Rouge' ('red Cambodians') is what Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk called them *(1989_3_05) and which caught on in the English-speaking world, not something they called themselves.

NOTE: For simplicity/clarity, I will follow the widely used label of "Khmer Rouge" for the CPK/Angkar, and refer to them by the abbreviation "KR". Since the higher-echelons knew it as the CPK, but the lower-echelons only knew it as "Angkar" (though they knew of it as the CPK after, it seems "Angkar" remained it’s predominant name), the "outsider" term KR is less tangled-up in these intricacies. It also helps with clarity I guess, since everyone (in the English-speaking world at least) knows of them as the "Khmer Rouge".

All of this has raised obvious questions, like: were they "actually" communist? If so, how much? And so forth. In short, the leadership did view themselves as "communists", though their understanding was extremely idiosyncratic, blended with their own backgrounds, dreams of reviving Khmer national glory, as well as French Revolutionary ideas. Except for a few at the top, no one read any Marxist texts, for example; the few privy to the "communist" nature of Angkar only learned orally (and often quite a limited understanding). But these were few. As far as the rank-and-file of Angkar knew, they were part of a revolutionary nationalist army. Had it just been that, it’d hardly be unique in the Cold War Third World. But for Pol Pot, this was the organization through which the "first actual attempt" at communism would be made (China’s Great Leap Forward (GLF) too little for him). The country would be sunk into pure agrarianism, an experience which alone - without any ideological direction (or even ideologically silent guidance from knowing cadres) - was supposed to organically yield communism, once the colonial ways of thought had been expunged. The people, even the Angkar rank-and-file, need not know anything, not even really who was leading "the organization". The result wasn’t utopian communes, but the local despotism of KR cadres - the smallest infraction could result in execution. Bridging the vast contradiction of an otherwise standard revolutionary nationalist army (if exceptionally unruly) unknowingly bringing the country (also long unaware of the "communist" nature of what was happening) to national revival and the "world’s first communism", mentality - rather than socio-economic factors (or both) - became the measure of man.

So if not planning, guiding, or anything such... what was the KR leadership doing? They were not so much directing a revolution. To do so would violate a central principle of the upper leadership: absolute secrecy. If the people were told to do anything beyond work hard, of course, the "enemies" (outside and within) could bring them down! (It’s worth noting a fairly obvious point: even at the height of Stalin’s Great Terror and Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (GPCR), the people certainly knew there was a communist party ruling, that the goal was to build communism, and so on; one at least had the "privilege" to know who was at the top, and what kind of system they were in, and even against what metric, however flimsy the charge, they were incriminated against) Yet despite this secrecy-proofing of their movement, to the KR, there were "enemies within" everywhere. Dealing with this was therefore the primary expression of KR central governance: ceaselessly hunting down dissident "strings", waging a relentless terror, growing more frenetic as war with Vietnam became more and more inevitable - a terror which most Cambodians did not even know where it was coming from, or why (apart from not working hard enough to their local cadre’s satisfaction). While 'terror' was common enough in ML (and other) countries, the KR’s scale and intensity was not (ie around 1m dead in the Great Terror (0.6% of 1937 population); around 1-2m dead in the GPCR (0.1%-0.3% of the 1966 population); by contrast, the violent deaths in the DK, estimated at 0.5m-1.0m, were 6.3%-12.5% of the 1975 population). And the KR’s mania for secrecy meant effectively no direction was given to the lower-level cadres, even in the most urgent moments. Thus, while they had a year to prepare, they never prepared guerrilla units to resist Vietnam’s invasion. When the KR leadership evacuated the capital, virtually no one but the evacuees themselves knew of this.

What isn’t "complex" is the KR’s horrific toll - though gauging the toll is. Per u/ShadowsofUtopia of r/AskHistorians, Ewa Tabeau’s and They Kheam’s (2009) Demographic Expert Report gives the general, contemporary consensus: around 1.747-2.2m - and as u/ShadowsofUtopia elaborates, around 1/4-1/2 (500k-1.1m) killed by execution (see that link for discussion of the killing-mortality uncertainty range). This in a country which had about 7-8m people in 1975. Important Note: in their answer, u/ShadowsofUtopia provides a currently-dead link to the webpage with Tabeau’s and Kheam’s report; you can view the original page on webArchive here; the actual report file can be accessed here.

However, a demographic balancing equation (DBE) approach (of which Tabeau and Kheam are skeptical; we will discuss) - which tries to separate "normal" from "excess" deaths when analyzing mortality crises - yields a much lower estimate, though still terrible, from 1.025m - 1.259m. Why the major discrepancy? As we’ll discuss, it comes down to the extremely violent nature of KR rule. If someone was "destined" to die of dysentery in 1975 (the "natural" death), but was instead executed for a small infraction by a KR soldier, that wouldn’t be a "natural" death, but one due to the KR. The extremely violent nature of KR rule, in combination with famine conditions and the general lack of meaningful economic planning (which is the lifeblood of any system at least purporting to be "Marxist-Leninist"), mean that it’s legitimately questionable if we can refer to a "baseline" mortality rate to compute an "excess" mortality. In this sense, KR-rule is something truly astonishing: neither "just" a famine, "just" terror, as murderous as "genocide" is popularly thought of, yet not a genocide. Considering the uniquely terrible character of this mortality crisis, I’ll refer to it in the text as the Cambodian holocaust.

Yet, we colloquially do consider this a genocide. This comparison, in my view, was a breakthrough for the HGS: with both the USSR-Vietnam and US litigating the KR as genocidal (though the US had an awkward position in the 1980s), it was going to end up reckoned a genocide. But increasingly, Vietnam tilted its rhetoric into the the HGS perspective thereof, which helped solidify this perspective espoused by the US at that time. So, today, we typically view the KR as the exemplar of 'communist totalitarianism'. Yet a closer look at the KR shows the assumptions in that label are quite fragile.

E.1. Who Were the "Khmer Rouge"?

In April 1975, New York Times correspondent Sydney Schanberg was stationed in Phnom Penh - that same month, the KR would take the capital and completely drain the city of residents. Schanberg, with the help of one Dith Pran, was in Cambodia covering the civil war that ensued since a US-backed coup, amidst secret bombings of the country, overthrew Prince Sihanouk and installed general Lon Nol. This was a brutal civil war, and the cities had become swollen with refugees - in 1971, Phnom Penh’s population was around 1.2m; by 1975, about 2m (source).

When Schanberg talked with KR soldiers - black clad with Mao caps and Ho Chi Minh rubber sandals - he couldn’t glean much information. One officer said he '"represent[s] the armed forces"', that 'there was only one political organization and one government'; some military units were called "rumdos" ("liberation forces"). Yet 'neither this commander nor any of the soldiers we talked with ever called themselves Communists or Khmer Rouge (Red Cambodians). They always said they were liberation troops or nationalist troops and called on another brother or the Khmer equivalent of comrade'. From what he could tell, the soldiers technically thought of Prince Sihanouk as the head of state, but just as a figurehead; the main name that came up was Khieu Samphan (1975_5_08). Later it would turn out, he too was more a figurehead, though certainly more involved in KR politics both before and after 1975.

Ultimately, like all foreign press and diplomatic staff, Schanberg was evacuated from the country. Dith Pran was not so lucky, barely escaping with his life from KR rule years later, his story the subject of the 1986 documentary-film The Killing Fields. But Schanberg’s observations are indicative of the elusive organization which took control of Cambodia in April 1975.

So, what was the KR?

The hegemonic perspective today is that (A) yes, they were "communist", and (B) their nightmare rule shows the last-stop of Communism is a dystopian totalitarian society, just like the Nazis. The moral equation with the Nazis seems basically obvious - during their rule, perhaps a quarter of the 1975 population died. But as we’ll see, such an equation is difficult. Not only for the issues of fitting 'totalitarianism' to Nazi Germany, but because - aside from their purging paranoia - KR rule of Cambodia was violent and harsh, but hardly 'totalitarian'. It was instead chaotic, overwhelmingly localistic. While it aimed to wipe old identities away for a new revolutionary one, it did so through perhaps the least totalitarian means possible: a political leadership which had only a hazy idea of the loyalty of the regional ('zone') commanders, no cult of personality, and cadres who didn’t know they were supposed to be communist. In short, their rule displays the characteristic phenomena of the 'totalitarian' model, but pursues its goals and produces this phenomena through thoroughly non-'totalitarian' means.

As I’ve argued throughout, 'totalitarianism' operates like a secularized heir to Orientalism. It provides a seductive rubric to categorize 'bad states', the risk of non-Western-approved ideologies: a hyper-despotic state which seeks to not only obliterate nationalities, but individuality itself. This concern for individuality is fitting, considering 'totalitarianism', though developing as a model in the 1930s, came into its own in the postwar era, in which the 'minorities-as-groups' (and [essentialized] 'groups' in general) concern of the League of Nations was superceded by the 'individuals-as-minorities' (and 'individual' in general) concern of the United Nations. With this new individualist anxiety in humanitarianism - though ironically subordinated to the groupist, Interwar-rooted concept of "genocide" (though in a sense, this helps bridge the two great Others) - 'totalitarianism'’s focus on 'ideological Big Brother trying to destroy individuality through a hyper-powerful state' becomes a clear, secularized heir to Orientalism and its Asiatic Despot, the tyrant over nations.

With this in mind, it’s particularly important not to succumb to the seductions of Orientalism or Totalitarianism. What is seductive about Orientalism is the fact that, indeed, the Ottomans did struggle against nationhood, that they did conduct themselves in ways that matched the phenomenology of Orientalism - of course, Orientalism was a 'model' to explain these observations. But Orientalism is a near useless guide to understanding the causes within the Ottoman state that produced these phenomena. Likewise, Totalitarianism is a model which sets out to explain particular phenomena from ideological states - namely, phenomena that the West negatively defines itself against. Almost necessarily by construction, such states will produce these phenomena. But as is the case in most (perhaps all) cases described as 'totalitarian', it doesn’t actually explain why these things happen, and tends to flatten out wide differences in the causal structure of such polities.

With Cambodia, both Orientalism and Totalitarianism are highly seductive; perhaps their fusion is embodied in Apocalypse Now. But while understanding the KR requires accounting for their specific context (one indeed in the so-called "Orient"), and requires accounting for their ideological background, we’ll find that the thing itself little reflects how Totalitarianism or Orientalism would predict it operate. Pol Pot was hardly a salacious Asiatic Despot, nor a ubiquitous Big Brother with a powerful state.

Before attempting to pidgeon-hole the KR into an ideologically convenient category, we should take a step back and try to assess them for who they were.

E.1.i - The Intellectual Background of the Khmer Rouge leadership. A central fact of the KR was that the leadership understood it as a communist party (of Kampuchea, CPK), but until late 1977, the KR rank-and-file did not. They were part of Angkar, in fact, they each were Angkar (some form of "one is all, all is one"). Nationalist? Yes. Revolutionary? Yes. Left-leaning? For many, probably yes (though the "left/right" spectrum may have been alien terminology for many). And revolutionary nationalism wasn’t itself anything strange, and more the bread and butter of nearly every Third World movement, from right-leaning ones to communist. Specifically left-leaning revolutionary nationalism also describes a wide range of Third Worldist movements of the Cold War. A major factor in the nature of the KR was their secrecy, fuelled by years of persecution (and the influence of individual proclivities of those making the names at the top). And this gave the KR many different faces, depending on who was looking.

To help distinguish these different faces of the same thing (the thing I call "KR"), I’ll use a few different names for the KR. (1) when discussing the KR in terms of the mass 'rank-and-file' that didn’t know about communism, I’ll refer to it as the Kampuchean Revolutionary Army (KRA), as per the 1976 DK Constitution, this is what the army was known as. Now most Cambodians had no idea that such a constitution even existed, so probably most members of the KR didn’t know they were part of something officially called the "KRA". Nonetheless, it helps make a distinction. Further, the spirit of the label isn’t entirely alien to the rank-and-file context: many cadres the Western press encountered did understand themselves as part of a Khmer/nationalist/revolutionary/liberation army. (2) When referring to the organization as a whole from a general Cambodian perspective, I’ll use Angkar ("the Organization"), as this is the name most Cambodians knew it as. I chose not to call the non-communist-knowing rank-and-file perspective "Angkar", as "Angkar" was also a legitimate name from the KR leadership perspective. (3) When referring to it in the terms the KR leadership understood it, I’ll call it the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). And (4), as I have so far, when referring to the organization in general, from a more "universal" perspective, I’ll refer to it as the Khmer Rouge (KR).

This plethora of names for different perspectives gives a sense of how unique, and self-defeatingly secretive, the organization was. By comparison, for most other organizations, a single label covers all of these (ie "Bolsheviks", "Republicans (USA)" ("GOP"), "Communist Party of China" (CPC), "Indian National Congress" (INC), etc).

Of course, sometimes communists opted for less bold denotations, in effort to rally a broad class alliance against imperialism, feudalism, and so on. Thus in the 1940s, this logic of resistance lead to Ho Chi Minh falsely claiming the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) had been dissolved, and that the liberation fight was a nationalist one (Short x77). And soon enough, in the 1950s, even this claim would come nominally true, with the ICP split into Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese branches, and each described in the less ostentantious 'democratic' vocabulary of post-Mao communist movements: the Lao People’s Party, the Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Party (KPRP), and the Workers’ Party of Vietnam - and in 1960, the KPRP would change its name to the Kampuchean Workers’ Party (KWP). Despite such national denotations, initially, as during the ICP, Vietnamese predominated in each of these - largely as they struggled to recruit qualified cadres of the other two nationalities. Yet for KR leaders such as Pol Pot, this reeked of Vietnamese ambitions of hegemony - a suspicion that would only grow with time.

Such ethnic resentment wasn’t itself that unique in the Third World at this point in history, or anywhere in the world for that matter. And the KR’s surrepitious naming scheme wasn’t itself that unique. What was unique about the KR was their ultra-secrecy: when they officially changed the name of the KWP to the "Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK)" in 1966, no one but the top leadership was made aware of this change - not until fall of 1977 would this start to peel back.

With the multi-faced nature of the KR denoted, we get to a key point about the KR. Insofar as we want to understand the guiding philosophy, we must look nearly exclusively to the leadership - of course, the rank-and-file perspective is valuable, but this won’t inform us of the 'communist' aspect nearly as much as it would in any other such movement. For the KR, at least insofar as we want to understand its "communist" nature (among other influences), its in the leadership we must nigh-exclusively look.

Up to the 1880s, Thai and Vietnamese polities had been slowly encroaching on Cambodia, long fallen from the glory days of the Khmer Empire - a glory ironically 'discovered' by the French, when they found Angkor Wat in 1860. But this local geopolitics was temporarily frozen in the late 19th century. Since the 1880s - with a brief Japanese interregnum - Cambodia had been ruled by the French. And thus it was to Paris that the most promising Cambodian students went off to study, including future stars of the KR, such as Saloth Sar (Pol Pot), Mey Mann, Ieng Sary, Thiounn Mumm, Khieu Samphan, and Hou Yuon. Like Beijing and Moscow, Paris is a city of awesome historical legacy, exemplar of a proud interpretation of modernity, and suffused with a revolutionary tradition; the duality of the Reign of Terror and the post-Napoleonic State. On top of this, in the 1950s it was the center of social and philosophical (ie 'existentialism') ferment. All of this contributed to the impressionability of the young Khmer intellectuals; in Philip Short’s view, it was like being taken to another planet (perhaps, to fill out his metaphor, one can imagine some Star Trek scenario, of 20th/21st century humans being transported to the 24th century USS Enterprise and its adventures, philosophy, technology, etc). It’s here that the future-KR leadership students had their formative introduction to revolutionary theory.

Initially, the radicals of the Association des Etudiants Khmers ("Khmer Students Association") (AEK) were split between those who backed a more purely Khmer liberation struggle under the banner of one Son Ngoc Thanh, who was exiled to France by Sihanouk (this group included Pol Pot), and those who supported throwing their lot in with the Vietnamese (this included Ieng Sary). At the same time, in the spirit of Ho Chi Minh obscuring the communist role in the Vietnamese liberation struggle in favor of a more broad-based nationalist one, the radical Khmer students felt likewise. For them, patriotism was a stronger rallying call. But then things started to change. Ieng Sary and his affiliates became more involved with organizations affiliated with the Eastern Bloc. And in October 1951, Thanh was de-exiled and returned to Cambodia, leaving a more-nationalist vacuum in Khmer Paris, strengthening the position of the left-leaning, pro-Viet Minh faction there. On top of this, the Khmer students observed that in France, it was primarily the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) which supported the liberation struggle. At very least, if they wanted coverage or discussion of the struggle at home (most French press focusing only on Vietnam, often conflated with Indochina as a whole), this was the way to go. All of this meant the AEK radicals took a dramatic turn towards the left - for those seeking a practical path towards Cambodian liberation, this pro-Viet Minh faction set the tenor.

Tapping into informal AEK political discussions groups, the Cercle Marxiste emerged as a secretive cell-based study/discussion organization. Imagine a [political] reading club, but organized like a 'terrorist' group. Ieng Sary - at the top, and one of the more self-identified with communist ideas (he had read the Communist Manifesto in Cambodian school before going to Paris) - ensured readings and discussions were focused on texts, literature, and topics from the Communist world perspective. Soon the members of the Cercle Marxiste signed up to join the PCF. In this way, like the KR to follow, a highly secretive organization formed in which a particular (and lacking for much core Marxist literature) form of communist instruction took place, at least for select Khmers considered sufficiently 'progressive'.

For most, actual knowledge of Marxism remained vague at best. The exceptions were Thiounn Mumm and Khieu Samphan (one might add Ieng Sary, insofar as he was one of two KR to have trained at the PCF Cadre School), and a generation later Suong Sikoeun and In Sopheap. In this sense, they were an unlikely group to lead a communist party (and did not lead one yet, but were part of the PCF). Yet like other communists around the world, Cercle Marxiste members were also aware of the works of Mao and Stalin (Pol Pot found Stalin easier to understand than Lenin); worth noting is that, contra our less rosy assessments today, Stalin was viewed rather charitably at the time (even the West had begrudging respect), given the Soviets’ decisive role in defeating Nazi Germany. Likewise, Mao was a rising star for Third World aspirants.

Philip Short cites three key texts for the Cercle Marxiste. The first two are Stalin’s 1938 History of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of the USSR†He also cites Stalin’s (1912) Marxism and the National Question, though noting that Stalin’s 'reject[ion of] the idea that a nation is a racial blood group' ran counter to traditional Khmer ideas; further elaboration on this text’s influence were unclear to me, though may have missed something. It seems ultimately, given the centrality of purging Vietnamese-by-blood people in the DK, these ideas didn’t seep too far. and Mao’s 1940 Yan’an speech On New Democracy - all the Khmer Cercle Marxiste students were familiar with these. Further, he cites Kropotkin’s The Great Revolution, which specifically left an impression on Pol Pot.

Stalin’s 1938 writing, in the wake of the Great Purge, emphasized the need for constant vigilance against opportunists within the Party; to purge them was to strengthen the Party. Of course, the document gives a ringing endorsement for a top-lead Party organization (characteristic of ML), as opposed to a broad-based party. Mao’s speech - crucial thoughts for Third World radicals - set the path for socialism, when starting from a colonized or semi-colonized/semi-feudal society, in terms of two distinct steps. The first step was a 'democratic revolution', lead by the peasantry with allied anti-imperialist classes (and establishing a 'new-democratic republic'), and the second step was the 'socialist revolution', lead by the proletariat - two steps which had to be distinct. Mao’s proposed first step promised a detour to socialism that didn’t require, per more standard Marxist thinking, passing through Western-style capitalism, since socialism was the dominant trend in the world at the time (thus making such a step more secure). In Mao’s view, the "yardstick" was the "revolutionary practices of millions of people".

Contrary to communists in, for example, Vietnam and China, there wasn’t any further study into Marxism, let alone the background philosophies that contextualized Marx (ie Hegel). For the young Khmer radicals, such texts as those mentioned above - bereft of their broader intellectual context - were the texts. [E1]Short (2004), Chapter 2

Yet they were not so alone in their interest in the 'new-democratic republic' stage, one which, on the surface, was a shared stage across the Third World (with non-Communist Third Worldists being content to remain at that stage). So, for example, Khieu Samphan’s doctoral thesis in Paris about Cambodia’s economy wasn’t so much "socialist", as it was a reflection of standard Third World economic nationalism. The thesis didn’t problematize capitalism as such (per On New Democracy, the bourgeoisie were an acceptable part of the class alliance), but foreign capitalism (ie of the colonizers), and emphasized the need for a native bourgeoisie. Such a heady mix under a communist banner wasn’t unique to the KR - Third World communist and socialist movements also had such (and was generally the thrust of non-Communist Third World nationalism). Both he and Hou Yuon made remarks about the need for autarky - but again, this wasn’t far out of place in Third Worldist currents (by 1975, the latter was considered 'excessively liberal' by KR leadership[E1]†he later died while incarcerated; but this probably wasn’t an execution, but due to a misunderstanding in the process; Short (2004), x387-388). Of the Paris students, Pol Pot had a qualitatively different vision about what this stage would look like. Nonetheless, the writings of those like Khieu Samphan would lay the basis for KR debates in the period up to their takeover in 1975. (CITE (x370-371?))

In Mao’s view, the shape of his two steps depended on the character of the country it took place in. But still, one necessarily gravitates towards the lessons of history to shed insight. Certainly, the conditions of the Russian and Chinese revolutions bore on the conditions for a revolution in Cambodia. But the group didn’t read about the history of the Russian (or Chinese) revolutions. For Pol Pot in the 1950s, the Russian Revolution was worth bringing up (if briefly) insofar as it too brought down a monarch (in China, the Qing were instead brought down by a revolution in which the GMD played a prominent role, alongside opportunistic reform-oriented Qing generals, such as Yuan Shikai. In the Russian Revolution though, it wasn’t the Bolsheviks in particular that brought down the tsar, but a broader worker uprising in "February" (March) 1917). There was a much bigger influence on this group: the French Revolution. They had all learned about the glory of the Republic, overthrowing the corrupt King, since they were in school in French-colonized Cambodia; and they were all now sudying where it began, in Paris. Thiounn Mumm, Ieng Sary, Khieu Samphan, In Sopheap, and Suong Sikoeun all have remarked on the influence of the French Revolution, even drawing specific parallels with France in the late 18th century and contemporaneous Cambodia. Ieng Sary, leader of the Cercle Marxiste, ensured it was a topic of discussion to draw lessons from. And in Paris, Pol Pot read through Kropotkin’s tome The Great Revolution.

Demonstrating the impact of The Great Revolution on him (beyond Short’s biographying), in the last year of his life, this was the single text he cited when recounting his intellectual background (1997_10_30_c). This per Nate Thayer’s reporting, who interviewed Pol in 1997, by which point Pol was under house arrest after being deposed - in the KR’s final, waning days - by Ta Mok (up to that point, Mok was one of few military commanders Pol could rely on, all the way back to the 1970s). Of course, we can’t discount ulterior motives for not mentioning the texts of Stalin and Mao, yet by 1997 no one substantively supported them, as the civil war "proper" had been over for awhile, and the USSR was gone - and with it, the US and PRC motive for backing the KR. So it’s hard to ascertain what political end this exclusion would serve, assuming the case that the two ML giants were disingenuously left out by Pol. Either way, that he remembered The Great Revolution in his final days (along with citations of Gandhi and Nehru) indicates its lasting impression on him. Pol would pass away on the 15th of April, 1998 - two days short of the 23rd anniversary of the KR takeover of Cambodia.

Short identifies three key arguments from Kropotkin that impressed on Pol Pot. One is a core alliance for a revolution to take off: the "current of ideas" from intellectuals which delegitimizes the king and provides a framework for a post-monarchical order, and the "current of action" from the popular masses (ie the peasantry) to bring about the disordered conditions to realize this model. Second is the need to carry the revolution to the end, arguing that bourgeoise elements had terminated the French Revolution halfway through, leaving it dangerously unfinished. Third is that the egalitarian principles of the French Revolution were in fact the very principles of Communism, to which Marx effectively added nothing†

(Desktop: Click the trigger text to make this popup stick; click elsewhere to dismiss)

Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921) can roughly be described as "materialist¹ anarchist", and as expected per the traditional Marxist-anarchist rivalry, he didn’t think highly of Marx². Perhaps his most famous book is The Conquest of Bread.

He was born into a Russian aristocratic family, though he renounced this background as his politics became increasingly radical; he was even imprisoned by czarist crackdowns in 1874, but escaped to Western Europe. He returned to Russia amidst the revolution in 1917, though was disappointed with Bolshevik rule. Kropotkin was also a brilliant biologist and geologist (probably among other competencies), the fields in which he originally made his name, and remained active in these throughout his life.

1. "Materialist" in the sense of believing in material (ie "socio-economic") causes (as opposed-to, or supplementary of, a causal explanation based on ideas/thinking/subjectivity), not "materialist" as in "consumerism".

2. Though not to say he criticized Marx purely for factional reasons; probably his critique is well thought out. Anarchists don’t oppose Marx simply because they’re anarchists - they’re usually anarchists as a result of their worldview, one at odds with a Marxian worldview on several topics.

. These arguments provided the structure for Pol Pot’s understanding of the France-Cambodia homology. And thus, the French Revolution, and the chief thinkers (to the Khmer students) of the revolution - Robespierre, Rousseau, Montesquieu, the Enlightenment in general - their guiding lights to revolutionary thought and action, within the broader rubric of Mao’s path to socialism and Stalin’s tips on running a Party.

From Stalin they recieved their idea of an optimal party organization, and the necessary vigilance against opportunists. From Mao they recieved the blueprint for achieving socialism, via a 'democratic revolution', one which must mind the character of the country it was taking place in - as well as the yardstick to measure revolution: the people’s revolutionary practices. And from the conditions of late 18th century France, they identified a situation of comparable conditions as that in Cambodia, and therefore a revolution to draw lessons from - for example, that the Reign of Terror had been cut short. All of this combined with their own background, specifically the feudal culture of Cambodia, and the thinking of Theravada Buddhism. From this, they inherited a prism to understand their readings: one of good vs evil. And in Pol Pot’s view, Buddhism had both been an opponent of the monarchy, as well as the first democratic system (ie Buddha abandoning his princely status to "become a friend of the people"). As a result, a monastic approach would come to characterize KR practice. With a final dash of admiration for Tito’s Yugoslavia (grasping the parallels of his defiance of the Soviet Union with their own aspirations to defy the Khmers old enemies’ (Vietnam and Thailand) - feared ambitions), this was generally the intellectual brew the Cercle Marxiste would take back to Cambodia.[E1]Short (2004), Chapter 2

What’s essential to note here isn’t the mere fact of Rousseau’s, Kropotkin’s, Stalin’s, or Mao’s influence as such, but how much their influence was bereft from a broader study of Marxism. Again, in this, the KR were unique as a self-identified communist movement, among those that truly wanted to go for it. While in the same speech Mao decries the use of formulas to achieve socialism, this, in effect, was the result of this limited theoretical basis. Certainly, the slogans found in pamphlets of Mao or Stalin or Lenin resonated with them - yet even as one can litigate how divorced these thinkers became from Marx and Engels over time (ie how 'Marxist' they were), they were all true students. Their thinking was part of a broader dialogue. The KR, by contrast, were not - their understanding of what 'socialism', 'communism', and 'Marxism-Leninism' were detached from the discourse which constellated their meanings; the conceptual gaps remaining from their sparse readings, interactions with other Communists, and so on, filled by their own concept-worlds. Now that doesn’t mean they aren’t a communist movement - such doesn’t need to be part of Marxist discourse; but that’s another question.

The oddball question here is: were they Marxist-Leninist? Whatever one’s thoughts on ML, the basic idea is that a vanguard party leads a nation through (at least) the socialist revolution. The vanguard should be educated, knowledgeable Marxists (and familiar with other thinkers of Marxism), and thus able to deal with a variety of issues from such an informed perspective - as well as interpret the arguments of fellow Marxists correctly (this is similar to how we imagine liberal politicians and civil servants should be familiar with Western philosophy, etc). With this interpretation, the leadership can ensure the party line is "correct", and is understood and followed "correctly". Yet we’ll find the KR lacks these basic requirements: there is a massive lacuna where Marxist knowledge should be. Further, the KR made a point of not informing anyone about what the party line was, other than to work hard on specific projects to strengthen the country and to be vigilant for "internal enemies". One of my hesitations in calling them ML, ML-Maoist, and so forth is rooted in these gigantic gaps - in their failing to core fulfill the ML criteria of a Marxist-Leninist party. Nonetheless, it’s worth considering that they, in some sense, at least thought of themselves in this general neighborhood of thought.

One is tempted to read them as "Maoist", but Short warns that much of these parallels are superficial. For Mao, the actual social conditions were of obvious importance, and in contrast, the KR never conducted any such investigation. Unlike the CPC or WPV/CPV, the KR leadership all had peasant and intellectual background, to the exclusion of a working-class one. Hence, contradicting the most fundamental identity of a supposedly Marxist party, they saw the actual, nascent Cambodian proletariat as anathema, and they even 'systematically refused admission to the Party'. Even in Mao’s most extreme moments, he believed the peasantry and proletariat should develop mentally and materially in tandem. For the KR, only the peasantry, when brought in Kropotkinian fusion with the intellectual leadership of the KR leaders, was a revolutionary class. For Pol Pot, this highly un-Marxist perspective was reconciled by turning to Buddhism, in which mentality alone - "proletarian consciousness" - was required for to proletarianize the peasantry, and thus address the huge anomaly in the CPK - a supposedly "communist party", that is, of the "proletariat", not being of the proletariat (in fact, in similar terms, Sihanouk called his own policy "Buddhist Socialism"). Short identifies the influence of Kropotkin - who saw the intellectual-peasant alliance as the basis of revolution which would yield an egalitarian communist polity, 'based on a refurbished version of the old revolutionary trinity, ‘[collective] liberty, [mass] equality and [militant] fraternity’, all endowed with a distinctive Khmer flavour.' By ignoring the material basis in socio-economic reality, and focusing on developing a 'proletarian' mentality alone, the KR elided the significant issue that peasantry and proletariat (at very least, within in classical Marxist thinking) were very different classes.[E1]Short (2004) x189

Sub-section summarizing remarks In my view, the most apt metaphor of KR philosophy’s relationship with Marxism and Marxism-Leninism is that of Islam to Judaism and Christianity. I don’t make this metaphor to make any value judgements about those religions (ie Islam is not the KR of the Abrahamic religions in the sense that the "KR were bad", just as a structural argument). The Prophet Muhammad lived in the trade city of Mecca, part of a trade route through Arabia which was dotted with, and travelled by, Christians and Jews - among other peoples and local faiths. Naturally then, he had heard the stories of these two faiths. But while Judaism and Christianity, roughly speaking, share the same text - the Torah/"New Testament" - the expression of these in the Koran is in a unique form that Muhammad wrote down. In turn, Islam saw itself as a 'final form' (so to speak) of a line of prophets, within which Jewish prophets and Jesus Christ came before. Thus, the two faiths were seen to have a relationship with Islam - fellow 'people of the book' - yet also remained textually quite distinct, and thus religions that didn’t fully/properly submit to God (though they had some protected status as 'people of the book'). Whereas Christianity emerged from a Jewish milieu (and Judaism obviously as well), Islam emerged from a more cosmopolitan world, and one in which maintaining the literal text of the Torah/New Testament was not a theological concern. Many of the stories and lessons overlap, yes. But it is textually distinct. In this sense, and only this sense, do I think some coordinates of the KR relationship with the broader Marxist world can be identified.

E.1.ii - The Cercle Marxiste Intellectuals Return to Cambodia, and the reign of the Khmer Rouge.

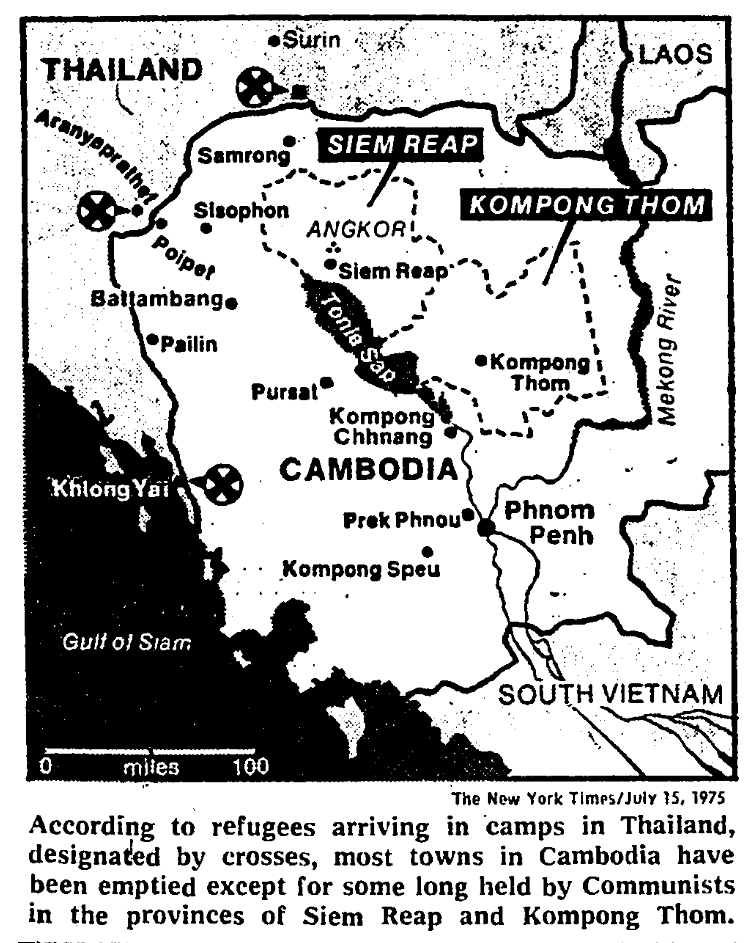

CAPTION (1);

Upon return, the young intellectuals entered an increasingly tense situation in Cambodia, part of the broader world of Indochinese revolutionary politics. A world in which communists were initially cautious to invoke the name of 'communism' in the liberation struggle, lest they alienate classes that might otherwise ally in the fight. Though this didn’t mean that the existence of communist elements was unknown in such movements; and communist symbolism was often a big (if not sole) fixture. Further, throughout the 1960s, Sihanouk’s crackdowns necessitated prioritizing secrecy; to the KR, this meant increasingly hiding their communist pretenses, a paranoia enhanced by their suspicion that the Vietnamese communists intended to dominate them after (and during) the liberation wars. Thus, when the KR leadership decided to change the name of the party from "Kampuchean Workers’ Party" (a standard one of Indochinese liberation struggle, bearing the stamp of Mao’s 'step 1' thinking) to the "Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK)" in 1966, they neither told the Vietnamese, nor the rank-and-file.

In terms of Marxist, or even Maoist, teachings, there were no books (during the 1975-1979 DK era, no time was given for the masses to read; cadres had only two journals available[E1]Short (2004) x412). They didn’t want any foreign influence on their revolution, which could taint its otherwise 'authentic Khmer doctrine'. This was an unprecedently mystical view of 'communism'.[E1]Short (2004) XXXX Short argues this, in part, reflects 'the orality of Khmer culture'. What top-level KR cadres learned 'about communism came from the senior student who led our ‘string’'. One cadre reflected that

[To us], communism meant the hope of a better and more just society. I joined the movement because I was against injustice . . . That was something that we heard about from the old people†The KR categorized people as 'old/base people' and 'new people'. 'Old/base people' were those, generally peasants, who supposedly lived untainted by colonial/Western influence. 'New people' were people, generally urban-dwellers, who had become more accustomed to colonial/Western ways of life.; they would tell us stories of how they had been oppressed. I wanted to overthrow the government, and that was the goal that Angkar — the revolutionary organisation — was striving for. Maybe I didn’t have any clear idea of what kind of system we were going to put in the place of the old one, once it had been overthrown. But I knew I wanted to overthrow the existing government.

They weren’t only at odds with the Vietnamese communists in the sense of national struggle, but also in ideological outlook. After the Indonesian purge of the PKI (the Communist Party of Indonesia) in 1966, they felt vindicated in their secrecy, and that the Vietnamese line of 'alliance with the bourgeoise' would lead to the same fate as the PKI. Notably, such also implied a broader challenge to Mao’s 1940 sketch of post-colonial revolutionary republics: first 'democratic' (a class alliance, with the bourgeoisie included), and then 'socialist'. Such a verdict foreshadowed the direction of Cambodia under KR rule.

This came in April 1975. After a long, brutal civil war with Lon Nol (installed in a US-backed coup in 1969, overthrowing Sihanouk, who went into exile in Beijing and Pyongyang), the KR entered Phnom Penh. Their rule in the newly renamed 'Democratic Kampuchea' (DK) began with complete evacuation of the cities. To Westerners, the KR explained this not as pre-planned, but a response to them finding a shortage of food reserves, and a plan of "US lackeys to attack us". In fact, the evacuation was pre-planned (since at least October 1974), and there was adequate food-supply - and it was much harder to feed moving columns of refugees. Further, there was no "US lackey" plan. But there were spy rings, which he told Chinese journalists about, and the CIA did confirm that the evacuations had destroyed their espionage networks (x367). These weren’t the 'real reasons' though. Pol had cited the Paris Commune, arguing the proletariat didn’t sufficiently domineer the bourgeoisie, leading to their fall (a topic of discussion in the Paris Cercle Marxiste days).

Per a CPK Central Committee document, the goal, along with security concerns, was to remove students and intellectuals "from the filfth of imperialist and colonialist culture" and "the system of private property and material goods [was being] swept away" (x367-368). Characteristically, this thinking wasn’t part of public rhetoric. Behind all this, Short argues the deportations were not initially part of an effort to 'exterminate an entire class, whether town-dwellers in general or intellectuals in particular', it was never CPK policy, though some KR soldiers and grass-roots cadres interpreted it that way. Recall that underlying all of this was a policy to fulfill Step 1 from Mao’s On New Democracy: a 'democratic revolution' made by a broad class alliance; though arguably, they violated his warning not to combine Step 1 with Step 2 ('socialist revolution') in a single step. But violating the principles of Mao was no issue for a movement that saw Mao’s efforts as falling short. Pol Pot’s goal was to more generally 'plunge the country into an inferno of revolutionary change', where old ideas (and their adherents) would 'perish in flames', but Cambodia would emerge strong and purified, 'a paragon of communist virtue'; 'not to destroy but to transmute'. Pol saw the evacuations as central to the CPK’s strategy, one no other ML country had ever undertaken (x368).

With the towns completely evacuated, the CPK’s broad outline was to first focus entirely on agriculture, "key both to nation-building and to national defense", per Pol. The KR aimed at 70-80% farm mechanization in 5-10 years, and then on that foundation, a 'modern industrial base' in 15-20 years, and to do so with as little foreign aid as they could tolerate, mostly from China (x369). Autarkic attitudes were not unprecedented in the Third World; in fact, goals of developing a domestic industrial base were pretty characteristic.

Western social scientists in 1976 suggested seemingly similar measures for Thailand - 'relocation of the surplus urban population to the countryside; confiscation of unproductive wealth from the rich; and increased investment in agriculture.' David Chandler, in that time, said "autarky makes sense". American Joel Charny, heading Oxfam operations in Southeast Asia at the time, said Pol’s 'rural development plans – digging irrigation canals, clearing new land for rice and mixing biofertilisers, with minimal use of fossil fuels and virtually no imports — ‘were they found in a consultant’s report, would win the approval of a wide cross-section of the [Western] development community’.' None of these were left-wing, and all saw that 'conventional development strategies' had failed in Cambodia in the 1950s and 1960s.

Further, on paper, the planning goals were reasonable: 3 tons of rice paddy per hectare, similar targets as those set by Sihanouk. Yet historically, average yields were barely over 1 ton of rice paddy per hectare, 'among the lowest in Asia'. To actually achieve this would require chemical fertilizer; in lieu of this, they used natural fertilizers like manure, but these were insufficient. The 3 ton target set the DK up for failure (x388-x389).

What set KR policy apart certainly wasn’t its technical policies (given the aforementioned endorsements), nor its extremism as such, but per a French specialist, it was 'just "cruel and inhuman"'. Short notes that even in the most extreme points of other ML countries, workers were compensated with some form of wage; this wasn’t the case in DK. For Short, the DK was 'literally' a 'slave state' (x370-371). Further, the KR decided not to use paper money - something which no ML state had done (perhaps save for extraordinary conditions, such as amidst civil war). Their argument was paper money promoted private property and anti-collectivist attitudes, and that the presence of paper money had entrenched the state as a private class in all the other ML states. Instead, DK exchanges would be mediated by barter. The result was completely dysfunctional 'state planning'; when Thiounn Mumm arrived in Phnom Penh from Beijing, he was horrified to find the Industry Ministry kept no accounts. When someone arrived to ask for something (ie oil), they would just be directed to the factory supposedly responsible for that good (though factories, as part of the cities, had been drained of workers and bourgeois specialists - 'new people' - rendering them generally ineffective), and kept no record of the supposed transaction. Often enough, the person sent to the factory wouldn’t find what they were looking for (ie oil). This was a situation of Pol’s creation: there was both no records, and no qualified workers or specialists in the factories, as people without a revolutionary background weren’t employable. He reveled in the fact that while other ML states might spend 'half' their budget on defense and construction, 'half' on paying wages, in Cambodia, they spent 100% on defense and construction, which "puts them half a million riels behind us". Those with economic training, such as Thiounn Mumm and Khieu Samphan, 'kept their mouths well shut'.[E1]Short (2004), x389-392

In an August 1975 visit to the countryside in the Southwest Zone (commanded by the reliable Ta Mok), Pol came face to face with the fact of food and medical shortage. This took a drastic toll on the people, particularly the deportees. But what bothered Pol Pot wasn’t this (and the associated suffering and mortality), but the affect it had on labor output. Part of the issue is that the cities had been drained without coordinating where the refugees would ultimately land, and thus most ended up in the East, Southwest, and Northern Zones. Pol decided the best course then would be to resettle around 1m people (told they were 'returning home') in the Northwest Zone. The policy itself was fairly sound (if despotic), the northwest 'traditionally the rice-bowl of Cambodia', with many sparsely populated areas at the time. Thus it made some sense - all else equal - for more people to live and work there, to increase national food output. But the immediate problem was that, during the major monsoon growing period (late-May—July planting, December harvest), the Northwest Zone had planted with its original population in mind. When the ~1m arrived at the end of 1975, it was far too late to grow new crops - in fact, the opposite was the case, since it was then harvest time. Thus the Northwest Zone’s harvest was stretched abysmally thin (and the 1m didn’t get to eat the crop they had planted in their original zones). For the KR, the population was just like oxen, an instrument. [E1]Short (2004) x392-x394

KR intellectuals that returned to Cambodia from abroad, though living better than most, help give a portrait of life in a DK commune. The chief priority wasn’t meeting growth quotas, but changing one’s mentality. Chiefly, a fierce opposition to private property (in part Short argues, 'rooted in the Buddhist creation myth'). As Khieu Samphan warned these arrivals, private property was more dangerous as a mentality, than a material reality; all things one thought of as 'yours' (ie your family) should be 'ours', Angkar’s (which was now the mediator of marriage, illicit love affairs a crime punishable by death[E1]Short (2004) x412). Once this private property materiality and mentality were destroyed, all would be equal. "If you have nothing — zero for him and zero for you — that is true equality ... If you permit even the smallest part of private property, you are no longer as one, and it isn’t communism." Yet he also tells the intellectuals to keep this to themselves, as it could discourage the masses. 20 Years later, Visalo still felt this was all just, since "Cambodians are naturally attracted to extremes"; Short notes here the resonance of Pol Pot with Kropotkin’s assertion that the French Revolution shouldn’t have stopped halfway. In this view, Mao himself - by 'allowing the need for wages, for knowledge and family life' - was guilty of such halfway-ism. The aim of this was 'destroy the personality' ("property of the bourgeoisie"), via 'a "surgical strike" to destroy "the individual", who, in contradistinction to "the people", defined as the embodiment of good, was seen as the root of every imaginable evil'. Through self-examination and public confession, would emerge a 'new man' 'who embodied loyalty to Angkar, alacrity, and non-reflection'. Laurence Picq, a Frenchwoman and wife of Suong Sikoeun, compared the experience to the South Korean religious cult 'the Moonies'. Hunger, lack of sleep, and long work hours contributed physical pressure to this indoctrination. [E1]Short (2004) x400-403

Short notes that 'no other communist party — whether in China, Vietnam or North Korea — has gone so far in its attempts directly to remould the minds of its members'. For the DK, they would

push[] the logic of egalitarianism, co-operative self-management and the withering away of the state to its uttermost limits. The ideals of the French Revolution, the practices of Maoist China, the methods of Stalinism, all played their part. But the specificity of Pol’s revolution lay in its Khmer roots. The destruction of ‘material and spiritual private property’ was Buddhist detachment in revolutionary clothes; the demolition of the personality was the achievement of non-being. ‘The only true freedom,’ a study document proclaimed, ‘lies in following what Angkar says, what it writes and what it does.’ Like the Buddha, Angkar was always right; questioning its wisdom was always a mistake.

Such conditions were similar - but far harsher - for town-dwellers (especially for 'the "Chinese", the Sino-Cambodian businessmen who had no rural roots', dying in larger numbers). The main doctrinal difference in rural Cambodia from the intellectuals was a focus on making 'deportees shed their bourgeois outlook and think and act like peasants', rather than demolish personality[E1]Short (2004) x409. Once eradicated diseases reared back up. For the first year, food supplies were meagre but not starvation-level. Still, the local-level variation in quality of life meant many had a brutal experience, with around a third of deportees dying by the end of the year.[E1]Short (2004) x403-405 Illness became associated with opposition; rural clinics were manned by untrained nurses of traditional medicine. At the same time, the combination of hunger and 'non-existent health care' was a tool for cadres to control subjects categorized as 'new' and 'base' people. Life was, generally speaking, tolerable for 'base/old' people, and this was theoretically supposed to motivate 'new' people to work hard to gain full political rights for a tolerable life (though, given the localism of cadre rule, it rarely worked out that way). The food shortage though, was real; new people starvation in the winter wasn’t an intended outcome, but a result of a broken system. In fact, Pol was obsessed with rapidly growing the population, wanting to double, even triple the population within ten years to 15-20m. Yet given the hardships, women couldn’t even menstruate. The KR leadership recognized the contradiction here. But at the same time, the country depended both on the loyalty of local cadres and the military - and so they had to be fed especially well (ie access to meat or fish). And in practical terms, the easiest means of discipline available to cadres was hunger, with the 'new' people drawing the shortest stick, and hunger a 'punitive weapon' and disciplinary tool (along with execution and terror). There was a fundamental contradiction with KR demographic (let alone political-economic) aspirations, and the practicalities of rule in the DK system. One solution the KR turned to - and one far insufficient - was drawn from the French Revolution: one day off every 10 days (this also would help reduce the caloric demand of the population). Generally speaking, these days were used for 'political meetings'.[E1]Short (2004) x406-407

'Indoctrination' itself was quite mild for a supposedly ML country, partly a 'conscious decision', since the fact that Angkar was actually the CPK was still secret, and only a third of the co-operatives had Party branches (by the end of 1975, actual CPK membership was probably only around 10k). As put forward by Khieu Samphan, the KR leadership didn’t think the masses were 'yet ripe for communist ideas'. Instead, 'nightly lifestyle meetings' focused on scheduling (ie planting) and technical reviews (ie fertilizer production, irrigation channel status, disciplinary violations). This pure, technical agrarianism was supposed to reforge the 'new' into 'base' people, establishing the basis for the next, aimed-for stage: instilling 'proletarian consciousness' supposedly necessary for the modernization of agriculture and industry. This was to be achieved through 'illumination', a Buddhist term which the Vietnamese had also invoked in the same role, but only as a metaphor. For the KR, it was literal, 'in its original Buddhist sense'. Rather than evaluating the country based on a Marxist focus on the economic organization of the country, mentality was instead the metric of revolutionary progress. 'For now, the nightly message was ‘to work hard, produce more and love Angkar’, to ‘build and defend the nation’ and to reject the selfish, individualistic values of Western-style capitalism.' Village leaders recited their lines like an incantation; the design 'like a Buddhist sermon, to ‘impregnate’ people’s minds so deeply with a single idea that there would be no room for any other.' Over Radio Phnom Penh, Pol Pot ordered the voices to be "like the monks who lead the prayers at a wat". The message was also delivered in the form of song, an aid to memory. Also Buddhist-inspired, these called for ‘renunciation’, devoting one’s body and soul to the collective without personal interest. Language was stripped of 'incorrect allusions', such as 'we' instead of 'I'. [E1]Short (2004) x408-x409

As deeply influenced by Buddhism as KR indoctrination was, many temples were not spared, dismantled for iron or turned into prisons and warehouses (in which Short draws parallel with Cromwell’s New Model Army); the monks, dependent on charity, were regarded as parasites, they "breathed through other people’s noses". Within a year, considered a "special class" ('a singularly un-Marxist category'), they had been defrocked and sent to co-operatives or irrigation work.[E1]Short (2004) x412-413

The violent paradox at the heart of KR rule lay in its high priority of secrecy. For Pol Pot, the KRA - an army of revolutionary nationalists, and that alone - was "the organization" which would go the full distance, achieving "communism" as he understood it, putting to shame countries like China or Vietnam. As we’ve seen, his idea of Marxism was, at best, idiosyncratic, with the goal of reviving the glory of the Khmer nation, and looking to surpass even Angkor. For him, "Marxism-Leninism" wasn’t so much a guiding set of principles, as something which would naturally emerge from the people, manifesting the above set of goals, once they were immersed in his extreme revolution. Once both the feudal and colonial ways of thinking were expunged from the country (either by reform, or by dying (and increasingly, as Vietnamese and suspected Vietnam collaborators were purged)), cleansed by agrarian labor into which all Cambodians were baptized, "Marxism-Leninism" would spontaneously emerge from the mentality of the people. This cohered with the KR mania for secrecy. The people didn’t need to know about a thing called "communism", it would emerge when all were equalized under Angkar.

The dissolving of pre-revolutionary bonds extended all the way down to the family, with people separated both by age and sex. Once in a commune, people were entirely isolated, the only persons they knew as 'governing' representatives were village chiefs, perhaps district chiefs, and soldiers. There wasn’t even radio (loudspeaker equipment limited to the most prosperous communes[E1]Short (2004) x410) - Radio Phnom Penh broadcasting more for the world than Cambodia.

In practice, every commune was an island of its own, subject to the despotism of its KR cadres. The most functional aspect of this localism was 'feudalistic, patron-client relationships', which meant that villager leaders were concerned only with their village, not even adjacent ones. This 'made a mockery of central directives, as Pol was well aware', but these attitudes were too 'deeply rooted' for the KR to change.[E1]Short (2004), x405 Cadres who’s knowledge of, or commitment to, "communism" is at best doubtful, and more often non-existent. With all of this in mind, in such a condition, Short argues, the supposed equalization of Cambodians brought out the domineering attitudes suffused in the 'prior' traditional Khmer society. One in which hierarchy (like many societies) drenched the language (though formally, such terms were abolished); one in which one’s lot in life reflected the karmic merit accrued over past lives. Those below were those who’s past lives were not so meritorious; thus they have their suffering coming. 'The entrenched individualism of Khmer society', as Short puts it.[E1]Short (2004), x368

This local-level despotism was extreme, for several reasons. Chiefly was that - unlike that in Vietnam and China - military victory came relatively quick (ie the 1969-1975 civil war, vs the CPC’s long military struggles from the 1920s to 1949, and the Vietnamese communists’ struggle from the 1940s to 1975). This rapidity meant that KR leadership remained primarily political, rather than military. The KR military - ie the KRA - was never brought under Pol’s control as such, and thus wasn’t an army loyal to him. More so, different sections of the army were loyal to their commanders. This not only exacerbated the paranoia of the KR leadership amidst turmoil from 1975-1979, but meant the primary means they could ensure control was purging implicated/suspected cadres and re-settling cadres of a trusted Zone commander, usually the Southwest Zone’s Ta Mok, in suspected Zones. While one shouldn’t overstate an organization like the PLA as 'a monolith', it stands as a far more cohesive counter-example, both during the civil war, and during the development of the PRC after 1949. By contrast, the situation in the DK looked more like Republican China under Chiang Kai-Shek: nominally one country, but more held together from 1930 to 1949 by Chiang’s ability to manage the militarists ("warlords"). This was a deadly flaw for the DK, since the army was the organization which ensured, managed, and enforced KR rule from April 1975 to January 1979.

In the end, this lofty idealism and utter secrecy brought the KR down: any failure was blamed on not being sufficiently revolutionary, and thus nearly identically, working for "the enemy" (ie Vietnam). The primary means by which the KR leadership interacted with the population wasn’t dogma, it wasn’t planning or the promised distribution of goods, it wasn’t radio broadcasts, not even a cult of personality. Cambodians had virtually no idea about who ruled them - though, through only nationalist injunctions to work extremely hard for good times in the future, they were expected to usher in something far more radical than China’s Great Leap Forward (GLF). "Central planning" was more just Phnom Penh paranoiacally hunting down dissident 'strings', purging to an unparalleled extent, as it grappled with a military structure it didn’t decisively control. This relationship was a one-way looking glass, or as Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan put it, that 'Angkar had "as many eyes as a pineapple"'[E1]Short (2004) x459. Such was clear when the Vietnamese invaded: the KR leadership left the capital virtually without telling anyone. Top officers radioing in for orders received no answer. No guerrilla units were organized to harry Vietnamese forces. Even at the main prison/torture center, S-21 or Tuol Sleng - the heart of DK’s main form of "central planning" - its chief warden, Deutch, wasn’t aware he had to evacuate til the day before he did. Because of this, he and his staff had no time to pack up the documents; hence why we have so much documentation about the tortures held there.

E.2. The Death Toll and Demography

To better understand this mortality, let’s interrogate the referenced document, Ewa Tabeau’s and They Kheam’s (2009) Demographic Expert Report. The authors are highly skeptical of demographic balancing equation (DBE) methods, which are pretty standard for estimating bounds on crisis mortality - these try to determine how much of the crisis mortality was due to "natural" death, and how much was "excess". They provide some practical reasons for their skepticism - such as that DBE analysis requires inputs of many variables. In the case of Cambodia, such were only vaguely known until recent decades, rendering our understanding of Cambodian demography quite hazy. They also state something interesting, suggestive of a (seemingly) non-practical objection to DBE analysis: The category of natural deaths must be seen completely marginal under Khmer Rouge as life circumstances the Khmer Rouge regime created for their population prevented natural death and forced unnatural death instead (pg 12).

Nonetheless, it’s worth undertaking a demographic analysis. As we’ll see, it suggests about half of their mortality estimate. Yet at the same time, given how exceptional the Cambodian holocaust was (it wasn’t "just" a famine), their reasoning for the larger death toll is worth considering. Altogether, we’ll find the DBE approach largely harmonizes with their findings (the discrepancy bearing out as a difference in some demographic analysis inputs) - so long as we match their assumptions. This in turn helps reveal the exceptional nature of DK-era mortality.

| Year | Populationᵘ | Population-RLᵘ | Population-RUᵘ | Populationᵈ | PGRᵘ (%) | CDRᵘ | CBRᵘ | NMRᵘ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 4.329 | - | - | - | 2.37 | 24.4 | 47.7 | 0.4 |

| 1962 | 5.726 | - | - | 5.729 | 2.16 | 19.9 | 41.9 | -0.4 |

| 1969 | 6.616 | - | - | - | 1.90 | 17.4 | 39.4 | -3.0 |

| 1970 | 6.743 | - | - | - | -1.04 | 22.6 | 40.7 | -28.4 |

| 1971 | 6.674 | - | - | - | 0.67 | 22.3 | 40.9 | -11.9 |

| 1972 | 6.719 | - | - | - | 1.40 | 21.7 | 41.7 | -6.0 |

| 1973 | 6.814 | - | - | - | 1.13 | 21.8 | 39.2 | -6.1 |

| 1974 | 6.891 | - | - | - | 0.65 | 21.6 | 34.6 | -6.5 |

| 1975 | 6.936 | 7.000 | 8.000 | - | -6.18 | 85.7 | 31.2 | -7.1 |

| 1976 | 6.520 | 6.567 | 7.506 | - | -6.76 | 86.6 | 27.6 | -8.3 |

| 1977 | 6.094 | 6.123 | 6.998 | - | -1.79 | 31.7 | 23.1 | -9.2 |

| 1978 | 5.986 | 6.014 | 6.873 | - | -0.84 | 22.6 | 28.4 | -14.1 |

| 1979 | 5.936 | 5.963 | 6.815 | 6.209 ± 0.209 | 3.82 | 19.1 | 37.9 | 19.7 |

| 1980 | 6.167 | 6.191 | 7.076 | 6.590 | 1.02 | 16.5 | 48.0 | -21.4 |

Population reported in 1e6 ("millions"); ie 1950’s UN-WPP reporting of "539.2" is 539.2m people, or 539,200,000; CDR ("crude death rate") reported in annual deaths per thousand people (‰).

Some estimates of DK mortality are based on the assumption that Cambodia’s 1974 population was somewhere between 7-8m. So I’ve made a "Readjustment Lower" (RL) and "Readjustment Upper" (RU). For these, I’ve set the January 1 1975 population to 7.0m and 8.0m respectively. Then I iteratively calculate the subsequent populations based on the UN-WPP reported growth rate for that year. For example, the adjusted 1976 population (P_76) is computed as: P_76 = P_75*(1 + (PGR_75/100))

Sources: (1) ᵘ: UN-WPP 2022; "Population" from "Total Population, as of 1 January (thousands)" (2) ᵈ: data from the Demographic Expert Report; population: from Table 1 (pg. 4); 1962 is from the 1962 Census (held on April 17-18 1962); 1979 estimae is Tabeau’s and Kheam’s own, for January 1979; 1980 estimates from the 1980 General Demographic Survey, "with reference to the end of 1980"

Tabeau and Kheam observe that the DBE approach for evaluating excess mortality in a time interval is subject to multiple sources of variation, namely (A) the population estimates at the beginning and end of the time interval - call these Pᵢ and Pₑ; (B) the crude death rate (CDR), (C) the crude birth rate (CBR), (D) the net migration rate (NMR). That might seem like a lot, but there’s ways to narrow down the demographic picture.

First, given Pᵢ and Pₑ, one can infer a percent growth rate (PGR) between; or if between two non-consecutive years which are 𝑋 years apart, an average percent growth rate (aPGR). In either case, it must be true that:

Pₑ = Pᵢ × Exp[(PGR†or aPGR/100)×𝑋] (Eq. 1a)

Re-arranging to solve for PGR, we get

(100/𝑋)×[ln(Pₑ/Pᵢ)] = ln([Pₑ/Pᵢ]^[100/𝑋]) = PGR (Eq. 1b)

Really, the PGR (here, the percent growth rate over a year) is also an "average" of population behavior within that year. Whatever the case, the exponential equation (Eq. 1a) expresses something like an 'average' demographic behavior between the two time points "i" and "e". Further, it must be true that:

PGR×10 = CBR + NMR - CDR (Eq. 2)

This must hold, since CBR, NMR, and CDR are the only contributors to population change.

However, there are infinite combinations of vitality metrics compatible with this aPGR. For example, if the PGR = 1.0% (10‰) in a year (or in a less precise assessment, that’s the aPGR), that could be a result of {CDR = 30.5‰, CBR = 40‰, NMR = 0.5‰}, or {CDR = 46‰, CBR = 42‰, NMR = +14‰}, or {CDR = 7‰, CBR = 13‰, NMR = +6‰}. All of these paint a very different picture: the first would be typical of a peaceful agrarianate country experiencing relatively good health (for an agrarianate country). The second perhaps an agrarianate society experiencing war, with settler-colonists moving in. The third a prosperous "developed"/"First World" country also experiencing net immigration. Obviously then, even assuming we know the initial (Pᵢ) and end (Pₑ) populations in a time interval, not just any set of vitality metrics is actually plausible. Only one can be true, though generally the goal is more modestly to narrow down the vitality metrics to some plausible uncertainty range.

This is usually done by considering what type of society is at hand, contemporaneous surveys and reports on vital conditions (these may be themselves inaccurate, but can provide some reference), and records (and if we’re lucky, somewhat-reliable (or even reliable) Censuses) about population and vital metrics. For example, a national survey of women could report (A) the distribution of children born per woman and (B) the age distribution of women. Considering women, generally speaking, can bear children from age 15 to 45-50†setting the lower bound at 15 is not me endorsing child marriage; but, especially in agrarianate societies, such young childbearing is generally a historical-demographic fact, we can then make a meaningful estimate of CBR. If we are talking about an agrarianate society (especially in peacetime), NMR will generally be negligible (ie NMR ≈ 0‰). Thus, if we have an idea of Pᵢ and Pₑ, we can then make a meaningful estimate of CDR (or average CDR (aCDR) at least) in the intervening time period, by re-arranging Eq. 2:

CDR = (PGR×10) - CBR (Eq. 3a)

Or

CDR = ((1/𝑋)×[ln(Pₑ/Pᵢ)]) - CBR (Eq. 3b)

If we know the PGR (and given Pᵢ and Pₑ (populations at two points 𝑋 years apart), at least aPGR can be accurately computed), and if we can meaningfully estimate CBR, our CDR (or aCDR) will be reasonably accurate.

More generally (ie not assuming NMR ≈ 0‰), the re-arranged equation for CDR (from Eq. 2) is:

CDR = (PGR×10) - CBR - NMR (Eq. 4a)

CDR = ((1/𝑋)×[ln(Pₑ/Pᵢ)]) - CBR - NMR (Eq. 4b)

Taking account of all of available information and 'balancing' can help provide such demographic data. The UN-WPP generally does this, by taking in what data is available (and it seems quite deferential to official demographic data (which makes sense, in its effort to provide a meaningful "official" picture, though this is a distortion), though it often does refer to other scholarly work), and applying several demographic models developed by "founding" demographers, such as Ansley Coale, to help fill in the gaps (that is, agrarianate countries in Southeast Asia in the 1950s-1980s are expected to have comparable demography).

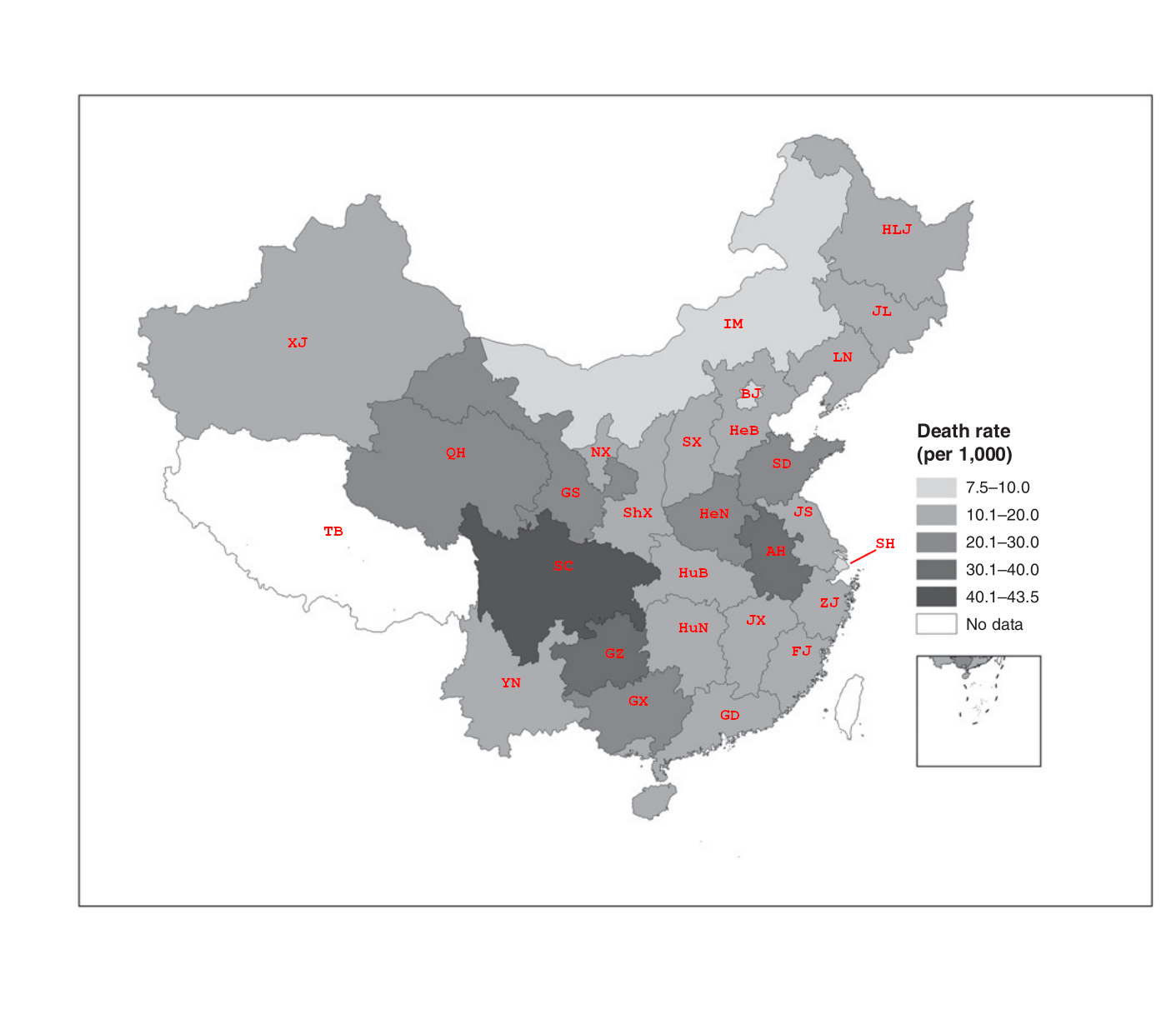

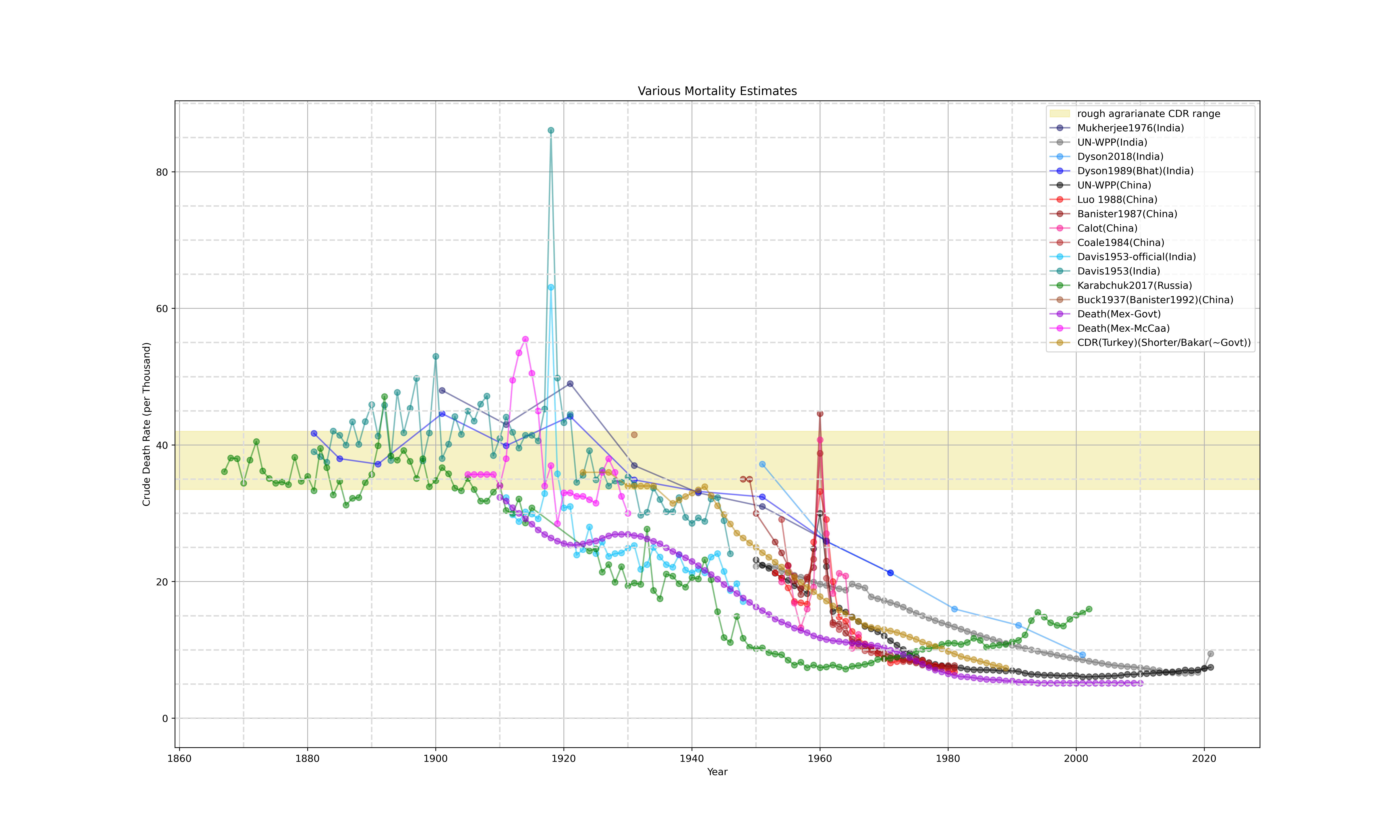

UN-WPP estimates themselves should be taken with a grain of salt, largely for their reliance on 'official' data. This is a good starting point (and again, it makes sense for the UN to rely on it), but most regional/country-specialized demographers - partially taking into account such 'official' data when available - often find a different picture. For example, these data tend to under-estimate demographers’ estimates for CDR in the PRC and India (the latter for which we have especially good statistics for a Third World country, due to British record-keeping and India’s commendable continuation thereof). For India, Dyson estimates a CDR of 32.4‰ in 1951, the UN-WPP estimates 22.4‰. For China, Banister estimates the CDR at about 35‰ in 1950, the UN-WPP estimates about 23.2‰. But the UN-WPP at least give a sense of trends (based on demographic modeling combined with official data and scholarly research where needed to "fill gaps"), especially in countries for which actual demographic data is lacking.

Considering the UN-WPP estimates for Cambodia, China, and India in the early 1950s, for example, suggests Cambodia’s then-CDR might have been in the low 30s‰, as is typical in agrarianate countries. Nonetheless, we can see by 1974, within the UN-WPP reported data, Cambodia’s CDR had barely fallen from the 1950 level, by just 2.8‰. Either way, as we’ll see, we don’t need to determine the "actual" values for Cambodia to analyze excess mortality during KR rule, so long as the systematic error for baseline and excess mortality are roughly similar .

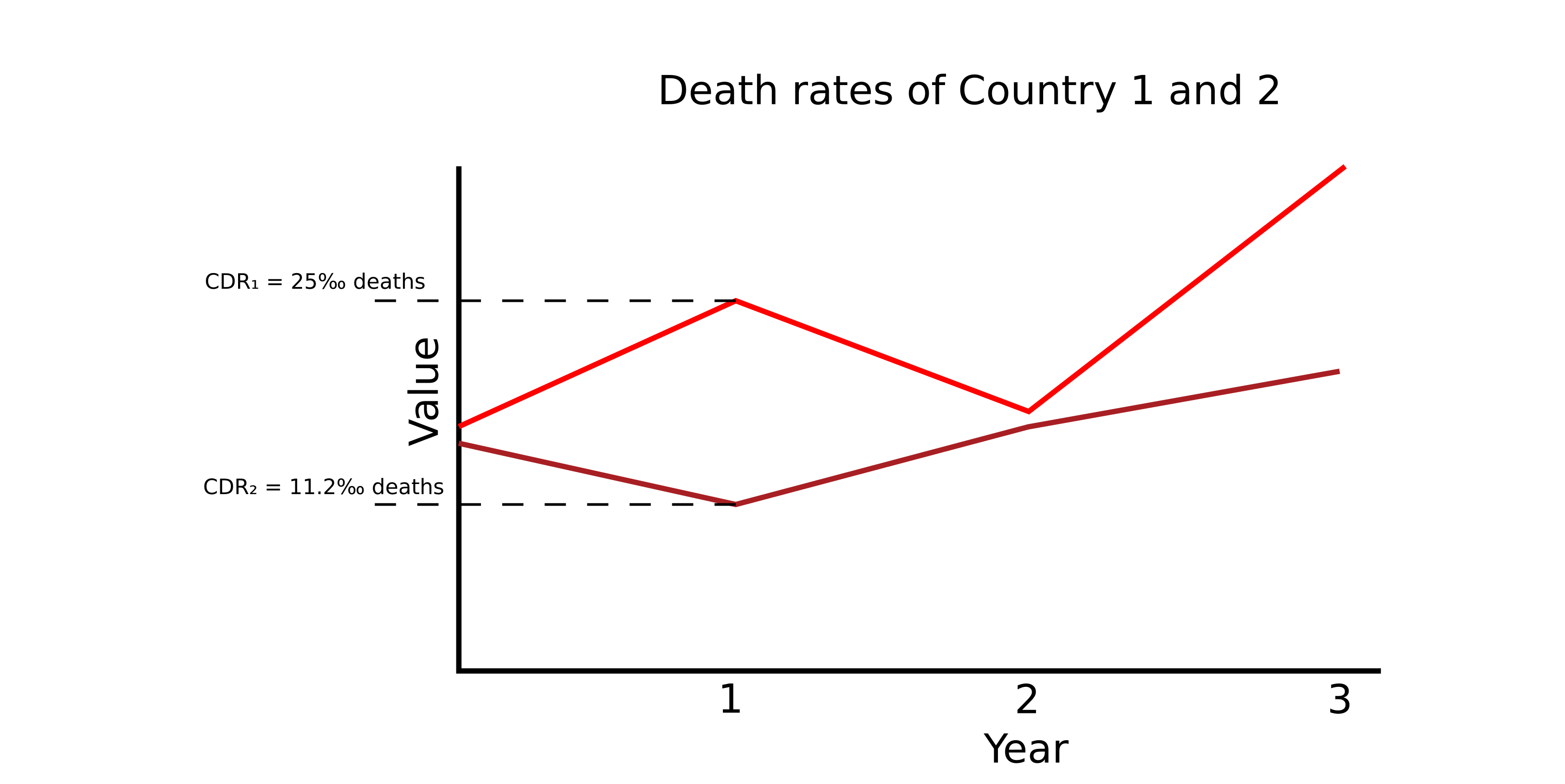

This all reflects real issues and responses in the DBE approach in general - particularly where data is sparse. However, if our goal is only to estimate crisis mortality over the baseline for a single crisis, the actual CDR values don’t much matter - what matters is the difference between estimated "crisis" and "normal" mortality, that is "excess" mortality. In general, "excess mortality" can be computed by a DBE approach by taking the difference of a baseline mortality rate (what the expected CDR would be if there wasn’t a spike in CDR, given mortality before/after the crisis) and crisis mortality rate. See the below slides (Though we would want these if we want to directly compare how well the KR performed to another country; so I’ll refrain from this, except insofar as we apply a similar excess mortality ΔCDR to the PRC during the GLF as the DK experienced, and with the general result - one that can be applied outside of demographic analysis - that about 1/4 of the population died due to KR action/policy).

Slides:

(1) suppose over several years, the red and dark red lines correspond to the crude death rates (CDRs) per thousand people (‰) in two different countries (call them CDR₁ and CDR₂ respectively). Though note that the CDR trend of country 2 could also be the expected CDR of country 1 in this time period (but for whatever reason, its CDR trend behaves exceptionally in this period).

(2) Suppose over those same years, the population for country 1 looks like this (call this population₁).

(3) The total deaths in country 1 can be computed as CDR₁‰ × (population₁/1000); for example:

► for year 1, CDR₁ = 25‰, and population₁ = 40,000,000 ("40m"); so total deaths = (25‰/1000)*(40,000,000) = 1,000,000 ("1 million").

► year 2: CDR₁ = 17.5‰, population₁ = 48m; total deaths = (17.5‰/1000)*(48m) = 0.84m

► year 3: CDR₁ = 34.1‰; population₁ = 55m; total deaths = (34.1‰/1000)*(55m) = 1.876m

This is shown on the bar graph as purple segments, although this is just for scale (and not to imply the population falls by that much per year, because it also gains a certain amount from births).

(4) Let’s zoom in, and plot those total deaths per year for country 1.

(5) If we take CDR₂ as our baseline, then we can compute the excess deaths based on the difference of the two CDRs (ΔCDR = CDR₁ - CDR₂, where "Δ" typically denotes "difference" or "change"). So, for example,

► In year 1, CDR₁ = 25‰ and CDR₂ = 11.2‰, so "excess CDR" is ΔCDR = CDR₁ - CDR₂ = 13.8‰. So then "excess deaths" account for 13.8‰/25‰ = 0.552 = 55.2% of total deaths for country 1. We can also compute the total excess deaths in a similar way as in step 3, with the equation Excess Death = (ΔCDR/1000)×(population). Here, that would be (13.8‰/1000)×(40m) = 0.552m.

► The difference ΔCDR is much smaller for year 2, so then the excess deaths in that year are much smaller. Specifically, CDR₁ = 17.5‰, CDR₂ = 16.5‰, so ΔCDR = 1.0‰. That means 1.0‰/17.5‰ = 0.057 = 5.7% of total deaths were "excess" for country 1, and total excess deaths were (1.0‰/1000)*(48m) = 0.048m.

► For year 3, CDR₁ = 34.1‰, CDR₂ = 20.2‰, ΔCDR = 13.9‰. Thus, 13.9‰/34.1‰ = 0.408 = 40.8% of deaths were "excess", and total excess deaths were (13.9‰/1000)*(55m) = 0.765m.

NOTICE: When calculating excess death toll, the absolute values of CDR₁ and CDR₂ don’t matter - what matters is the discrepancy between the two, ΔCDR = CDR₁ - CDR₂. Thus, if there is a systematic error which offsets both by the same amount from the "actual" values, then we can still calculate the correct excess death toll. In text, this is called the mortality shift viability.

(6) Over the period of interest, take the sum of these excess deaths for the total or "cumulative" excess deaths over that time interval. In this case, that would be 0.552m+0.048m+0.765m = 1.365m excess deaths.