"Burning of the cholera-stricken lighthouse neighborhood of the Tondo district, Manila, 1902, by the health authorities." (source; also Anderson (2006) "Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines" pg 64)

"Burning of the cholera-stricken lighthouse neighborhood of the Tondo district, Manila, 1902, by the health authorities." (source; also Anderson (2006) "Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines" pg 64)

See also:

I am interested in exploring the period from 1880 to 1955 precisely because it is in this period before modern medicine and urban sanitation could be expected to have been so important when the Soviet population experienced massive short-term demographic crises accompanied by secular improvements.

- Stephen Wheatcroft (1999), "Toward an Objective Evaluation of the Complexities of Soviet Social Reality under Stalin"

In 1933, famine and food shortage hit the Soviet Union hard, particular in the southwest region, the Ukrainian SSR and southwest Russian SSR. The causes are controversial - how much was it a result of reactionary sabotage? How much from hasty, violent collectivization? From over-requisitioning? From a declining agricultural output, as peasants moved to the factories? Regardless, this was a traumatic opening to the USSR’s rapid industrialization, which soon proved its value in WWII, or as it is known there, "The Great Patriotic War". Overall, the mortality rate of 1933 in the USSR was around 37 deaths per thousand people - or more succinctly, 37‰ - nearly double the normal rate, around 20‰ (in the West today, the death rate is typically between 5-10‰; then it was in the low 10s‰). Based on this difference of normal and crisis mortality rates, scholars estimate somewhere between 3-6 million died (the higher figures resulting from upwards adjustments of the death rate). For this tragedy - as well as the Purges - the legacy of the USSR has remained tarnished in popular memory.

Yet remarkably, the normal death rate - around 20‰ in the interwar period - had fallen about 33% since the Tsarist days, around 30‰ on the eve of WWI. The death rate would fall further still, to around 10‰ by the late 1940s, despite enormous damage from the Nazi invasion (during which all-Union death rates ranged in the 40s‰ to 50s‰ - 20m-30m Soviets died in the war, the majority civilian). All of this from a generally impoverished, agrarian country, building up basic medical infrastructure (among other social factors) of the pre-Penicillin Era, "Ante Aetas Penicllini" (AAP). Such measures included urban sanitation, more comprehensive water and sewage systems (Starks 2008), and hygiene and sanitation measures in the countryside, a large expansion in medical training institutes (with a focus on sanitation), maternity and infancy care, mass medical propaganda, vaccinations, health-based education, mandatory service of newly trained medical personnel in rural areas, and campaigns targetting diseases like malaria (Zamoiski). Overall, Soviet healthcare was particular effective in infant care and controlling infectious diseases (as well as expanding women’s education), drastically bringing down infant and child mortality rates (IMR fell from 265‰ births in 1920 to 168‰ births in 1939, most of this progress in the 1920s). Further, as the population urbanized (From 18% in 1913 to 15.3% after the civil war, to 18% again in 1928, to 32.5% in 1939), the health benefits associated with urban sanitation infrastructure became more generalized. In 1917, only 23 towns had sewage; in 1928, 43; in 1945 185. Municial water supplies: 215 1917, 292 1928, 512 1940. (Voskoboynikov).

None of these measures required any groundbreaking scientific developments over the prior century, except for disease-specific campaigns (ie anti-malaria), which were a result of the late 19th century medical triumph of germ theory. Particularly, infant care, control of infectious disease (ie by vaccination, sanitation), and women’s education - the backbone of overall medical improvement - were not scientific-technical novelties. They were social policies accessible to a 19th century administrator. Significantly, even as health did not receive overwhelming budgetary priority, it was nonetheless budgeted.

What was the situation elsewhere? How does it compare with the USSR?

The impact of colonial rule is, no surprise, highly controversial. On this issue, India remains a key 'laboratory' of debate, in part thanks to the one British virtue - great record keeping. Unlike other Global South regions which generally lack demographic data (except China), we have quite a bit of data about India in the 19th century and beyond. Around the turn of the 20th century, Indian nationalists argued that the British were 'draining the wealth' of the continent. Colonial apologists, naturally, argue that British rule was actually a net positive. Critics elaborate on the wealth drain argument. For example, did railroads drain the country of food in times of need, or did they facilitate the movement of food within India from surplus to deficit regions? The overall picture is pessimistic: death rates didn’t fall much compared to pre-colonial levels, and often spiked. Overall, it seems the British fared about as well as a pre-colonial administration, this in spite of the technical achievements its apologists proclaim. The natural question then is: could the British have ruled better, or was this the best possible given the technical capacities of the time?

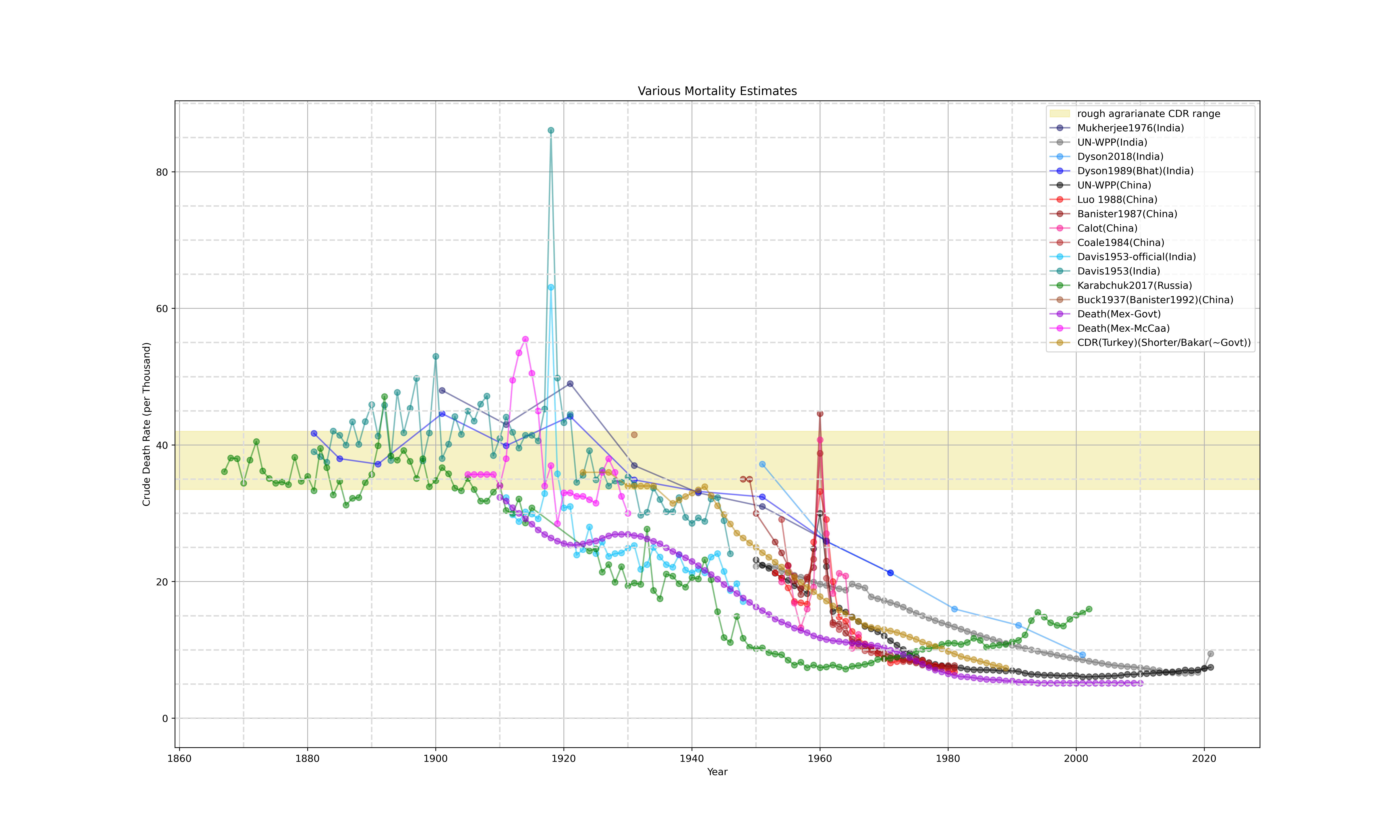

It’s here that the Soviet - and as we’ll see, Mexican - example is revealing. These were two poor agrarianate countries that still managed to substantially bring down death rates. Considering them throws the horrific conditions in the colonial and semi-colonized world in sharp relief: in India, the baseline mortality rate was 34.9‰ in 1921-1931, 33.2‰ in 1931-1941, and 32.4‰ 1941-1951. From 1880-1920, partly due to harsh El Niño, and just as much due to the capitalistic political economy imposed by the British, regular death rates ranged from 37.4‰ to 44.6‰; prior to this, death rates probably ranged from the mid 30s‰ to low 40s‰, although data is less precise for this period - probably the 19th century death rate was less severe than 1880-1920, and the interwar death rate more a return to this due to improving weather, than substantive welfare improvement. Notably, these were rates comparable with mid-19th century Russia - even the rudimentary rural health developments under the Tsar saw modest health improvements; in India, even by 1951, British administration had yet to match those improvements (British rule ended in 1947, but 1951 is the nearest year to that available).

In China, which was never directly colonized (outside of some treaty port settlements, and various interventions), death rates likewise ranged from the mid 30s‰ to low 40s‰ in the 19th century and up to 1949. China’s story is a bit more subtle. The degree to which ecological erosion, internal economic depression, and the 'drain' of silver from China to the West destabilized China by the mid-19th century is hotly debated. Nevertheless, in the mid-century, a series of violent rebellions exploded. Tens of millions died, and the Qing Treasury was largely expended on war, rather than on attending to infrastructural and granary upkeep. Along with huge debts incurred due to 'unequal treaties' - along with explicit interventions - the state had little capacity to respond to increasingly erratic weather in 1880-1920. Massive famines and droughts blew through parts of the country. Due to the breakdown in state bureaucratic capacity from 1851 to 1912 (and then, until 1949), it’s impossible to tell exactly what happened during that time, although overall population growth indicates no catastrophic deviations. Based on the baseline article, suggesting a baseline, non-crisis CDR in the low-mid 30s‰, the Qing performance was pretty typical of agrarianate societies. How it would have performed without these interventions is a whole can of worms.

In Africa, the picture is much more obscure. Yet the conquests of 1880-1920 brought up enormous labor dislocation, massive spread of disease, and brutal 'pacification' wars - in some regions, such as equatorial and central Africa, the population as a whole likely fell over that period. While it’s unclear what the baseline death rate was before colonization (and specifically, what it would have been without the effects of the slave trade), the baseline article argues that an underlying CDR in the 30s, even 20s, may be plausible, yet in reality unrealized, due to the political economy of the slave trade. The crucial point here is that the scale of the slave trade political economy resulted from commercial interaction with Europe, and didn’t endogenously develop - thus the actual death rates, which were likely higher, are difficult to untangle from the effects of Europe. In Latin America, the second half of the 19th century saw CDR in the high 20s to high 40s range (Argentina and Uruguay here remain difficult to parse, but appear to be below this). As we will see, active government policy brought down CDR in the region in the early 20th century, to the mid 20s to mid 30s range (outside the Rio de la Plata countries). In the Middle East and North Africa, the overall regional CDR ranges from mid 30s to low 40s.

In summary, baseline mortality rates - the "normal" level - remain in range of the Soviet crisis years! Despite complaints of the "white man’s burden", colonial regimes oversaw little to no improvement in the quality of life compared to their predecessors - the main "benefit" being the stability of "Pax Colonialis" periods, although such benefits were perhaps balanced out by the horrific "Bellum Coloniale" periods of subjugating war. The aim of colonial administration was to rule as cheap as possible - and a variety of medical ideologies were conjured up to justify the resulting neglect of the colonies - most notably, "Tropical Medicine". Perhaps the most horrifying pinnacle of this neglect, the spread of disease, this malnutrition, was the 1918 Influenza pandemic, in which tens of millions died across the Global South (and far disproportionate to the West’s toll).

The fundamental implication however, is that even relatively poor agrarian countries could harness the medical knowledge of 150 AAP to reduce death rates. In Egypt under Muhamad Ali (r. 1805-1848), vaccination and quarantine measures were put in place, as well as the development of medical training institutes. By the 2nd half of the century, these developments brought CDR down to 29.6-34.6‰, from 38.4-44.8‰ before. In Revolutionary Mexico, along with social factors such as land reform, public health budget skyrocketed from 0.8m pesos in the late Porfiriato years to 8.4m pesos in 1927 - a factor of 10.5 - cutting the death rate; this along with extension of public schooling to the countryside (Cárdenas et al. (2000) pg 136/147). This resulted in a shift from the mid-30s CDR of the Porfiriato to a CDR in the mid-20s, with a peak during the Cristero War and its afermath (1926-1929), and a steady decline after. The Soviet Union was not alone in its agrarianate AAP health progress, as these Latin American and MENA examples indicate. What was accomplished was, in a sense, a 'reproducable' result. Certainly colonial administrations were technically capable of this - not only did they have the know-how, but they were part of the richest polities in the world. Their failure’s then indicate a massive hidden death toll, one of neglect, recklessness, and over-exploitation. For example, if the Soviet model suggests similar efforts could bring CDR by 10‰, there was an excess death toll of 100m from 1921-1951 in the British Raj. For the interval 1881-1951, the same suggests 184m - and that’s not considering the CDR decline the Soviets saw postwar.

Yet more than a mere moral failing, these shortcomings reveal damning flaws in the political economy of the 19th century capitalist world: the drive for profit, for raw material inputs, for new markets, for food, for the cheapest administrations possible, lead to these results.

Meanwhile, western/northern Europe had been doing quite well - threats of revolution (and the occasional explosion) and popular movements, from suffragist to socialist, had pushed their governments to improve sanitary and medical conditions, despite the prevailing "laissez faire" attitude of 19th century liberalism. Sporadically over the early-mid 19th century, beginning with the French Revolution and finally mutilated in the Paris Commune, the spectre of revolution haunted the continent. While a resort to force was always in the cards, a more robust innoculant to social disturbance was required. One key element here was improvements in public health.

Thus, over the long 19th century, regular death rates fell from the mid 30s‰/high 20s‰ level to the low 10s‰ by the eve of WWI. While industrializing labor migrations from farm to factory would otherwise spell food shortage (a problem acutely felt by the early USSR), massive food imports from Asia, the Americas (largely at the expense of native Indians), and eastern Europe afforded western Europe a sustainable nutritional level (at the same time, primary commodity production from the Americas and the colonies fuelled industrial output). This is not to say life was great, but it was far better than that in the Global South, which was squeezed to fuel this very industrialization.

This is the necessary context for Wheatcroft’s observations above. The remarkable fact of the early USSR is not the phenomena of famine, but the steady secular improvement in quality of life. By the end of WWII, not only had the USSR developed the industrial base necessary for the Nazi defeat (with significant American aid, of course), but death rates were comparable to the West. Yet in 1914, the Russian Empire was only marginally better than China, India, Africa, and much of Latin America - and after the massive destruction of WWI and the civil war, was deeply impoverished. Still, it made incredible achievements in industrialization and basic medical infrastructure, plausibly within the capacity of the contemporaneous colonial administrations. And all of this in the Pre-Penicillin Era - "Ante Aetas Penicillini".

It should be no surprise that, in the Penicillin Era ("Aetas Penicillini"), elements of the Soviet model, if not its most radical dimensions, were incorporated into postcolonial governments around the world (five year plans were near universal in the Cold War; even the most reactionary states had them), and even motivated the modern welfare state in the West. More unsurprisingly (yet completely obstructed from popular memory), the positive results were best exemplified in the Marxist-Leninist People’s Republic of China. When compared to India (both starting at similar death rates and comparable conditions; and both developing largely on their own terms), the rapid welfare improvements in the People’s Republic of China indicate that hundreds of millions of Indians perished, as a result of its failure to pursue similar social improvement as vigorously. Yet despite these shortcomings, independent India was still a significant improvement over British administration - it was certainly far more active in its efforts to extend welfare security to the general population.

I demarcate a "Pre-Penicillin Era" ("Ante Aetas Penicillini") and "Penicillin Era" ("Aetas Penicillini") (divided roughly before and after 1945-1955), not to focus on penicillin as such (although it deserves much attention) - despite its immense medical value, antibiotics are not a Christ figure, not a Prophet of God, for the modern era (for example, observe that death rates in the West in 1950 were not much higher than today; in the [former] USSR, they were lower in the late 1940s than after its dissolution, up to today). Instead, as Wheatcroft above hints, medical treatment in these two periods was very different. In a sense, this confounds our ability to compare vital metrics, such as death rates, across the two periods. Thus the Soviet Union here (among others, such as Revolutionary Mexico and Khedival Egypt) is not only significant in and of itself, but because it shows what even a deeply poor country is capable of, in a backwards, agrarian country. Such reference points, I argue, throw the failures of colonial administrations, and laissez-faire faith in "the market", in sharp relief.

My argument is not to say that European rule was necessarily "worse" than its predecessors - although it certainly had periods which were exceptionally bad, and left unique structural scars that persist to this day. Rather, it is an interrogation of "the white man’s burden". Despite the amazing technical advances of capitalism, the social complexity of the world market system, the colonial powers did not in fact "fill full the mouth of Famine and bid the sickness cease". Rather than "seek another’s profit, and work another’s gain", they engorged themselves. Their rule was near indistinguishable from their "premodern" predecessors. They were certainly technically competent for the task - however, such necessitated a political economy oriented not towards profit, but towards the common welfare. As flawed as the 20th century Marxist-Leninist paragons were, they best fit this bill. Looking back, we can see this bill was not a "white man’s burden" - it was a people’s victory.

Perhaps it sounds ideological, propagandistic to say this - some might argue it is not the place of a historian (even the amateur) to make such moralistic statements. I reject this. There are some facts of history, such as the Haitian Revolution, emancipation and the Union victory of the US Civil War, and the defeat of Nazism and Fascism in WWII, that deserve to be stated black and white. While all of these histories were as flawed as anything (the full range of their promises and hopes often painfully unfulfilled), they are also deserving of unapologetic acknowledgement, lest we forget the magnificent, joyful potential of humanity in a chrono-sea of horror. These were all triumphs over massive social forces, often so deeply embedded, so powerful, as to grind down any hope they could be overcome. Yet they were. Of course, the naysayers, the conservatives, the reactionaries - in the face of the horrific tolls they defend - argue otherwise:

There were two “Reigns of Terror,” if we would but remember it and consider it; the one wrought murder in hot passion, the other in heartless cold blood; the one lasted mere months, the other had lasted a thousand years; the one inflicted death upon ten thousand persons, the other upon a hundred millions; but our shudders are all for the “horrors” of the minor Terror, the momentary Terror, so to speak; whereas, what is the horror of swift death by the axe, compared with lifelong death from hunger, cold, insult, cruelty, and heart-break? What is swift death by lightning compared with death by slow fire at the stake? A city cemetery could contain the coffins filled by that brief Terror which we have all been so diligently taught to shiver at and mourn over; but all France could hardly contain the coffins filled by that older and real Terror — that unspeakably bitter and awful Terror which none of us has been taught to see in its vastness or pity as it deserves.

Mark Twain (1889), "A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court"

Let us not forget that cold blooded, unspeakably bitter and awful thousand years terror.

In "The Price of Gradualism", we saw the differential mortality consequences of a gradual liberal approach, vs a radical ML approach, to reforming a poor agrarianate society during the Cold War. This was a period marked by scientific breakthroughs in crops and medicine. Naturally then, the question follows: what about before 1950? What were the health impacts of colonialism, and the introduction of capitalism around the world? For that, we’ll need a baseline. See here.

The important result of the analysis in the baseline article is to challenge the "Malthusian" demographic trend (MDT) - that high birth and death rates prevailed in the non-Western world until recently (say, until the turn of the 20th century to the mid 20th century, or there about). This would suggest that birth and death rates were both in the mid to high 40s/low to mid 50s per thousand (near the biologically maximum, as per the Malthusian hypothesis) since time immemorial NOTE This pre-modern period generally has birth rates and death rates near each other (whether at Malthusian levels or lower), leading to a low growth rate. From here, the "demographic transition theory", inspired by Europe’s demographic trends, suggests that death rates first fall while birth rates remain unchanged, thus a period of relatively low death rates along with extant high birth rates (call this the LDHB (low death, high birth) regime). This period is associated with a population boom, before birth rates fall, leading a low death, low birth rate regime (LDLB), and again recovering moderate/low growth rates. However, there have been deviations from this - for example, Latin America and Africa saw rising birth rates in parallel with falling death rates in the mid 20th century (LDRB), before birth rates began falling to a more moderate level (LDMB), leading to a sustained, enormous population boom. . What we see is, instead, birth rates that range from the high 30s to the mid 40s, sometimes in excess of 50, and death rates that are typically in the mid 30s to low 40s - this is referred to here as the "agrarianate demographic trend" (ADT). This is in reference to the general pre-capitalist conditions that were highly dependent on agrarian labor, which I prefer to "feudal", with its various connotations of medieval Europe that may not apply in other regions (a term I borrow from Hodgson in "Venture of Islam").

Crucially, we see that parts of the world saw death rates staying at this level in the late 19th century and early 20th century, sometimes even rising, and then steadily declining to the mid 30s to high 20s by WWII. It’s difficult to say if this represents a substantial improvement over the ADT, due to the large range of error associated with computing vital statistics for "pre-modern" times, although death rates in the 20s, even high 20s, are noteworthy. These aside, large parts of Africa, South Asia, the Middle East, China, and many parts of Latin America were still in the ADT around WWII. With this in mind, the significance of the ADT vs MDT is that an MDT baseline suggests this is an improvement, whereas the ADT suggests this is either a return to normal from high mortality, or perhaps a slight improvement, an issue of great historical - as well as political - significance when judging the public wellbeing efficacy of different types of government in this period, and thereafter.

It is tempting to try and calculate "excess mortality" based on the ADT of a region vs its more recent demographic performance (that is, when colonial and post-colonial data bears out more reliable vital statistics). However, I will generally refrain from this (except as corrections to other such estimates), due to the error inherent in computing the ADT - these are calculated not as a rock-solid reference, but to give a broader sense of where vital metrics lie (ie 30s vs 40s), and to give some substance to critique of the Malthusian hypothesis. However, we can make fairly reliable qualitative statements based on said ADT estimates.

In other words, if we are to judge the mortality of the colonial regimes in the BP era, we shouldn’t simply consider the agrarianate baseline - it appears they managed their population’s health roughly as well as a feudal emperor (as we’ll review, from 1880-1920, the excess death toll against the Mughal-era baseline is estimated around 60m (although there are issues with this estimate); for other periods, the toll seems more or less negligible). We should also consider the health gains possible by a feasible, yet radical, change in the social order, given the techno-scientific knowledge of the era. Quantitatively measuring this will necessarily remain quite speculative, but evidently the magnitude of this excess death - comparing modern vs modern social organizations, not modern vs feudal - is enormous.

If we reckon, for example, that Egypt and India India is a useful reference point, because demographic data after 1871 became quite reliable, giving us a fairly long-term demographic picture. Thus, it’s a fairly reliable comparison point for quantitative estimates (as opposed to many other regions around the world, until the mid-20th century) are comparable (there are geographic reasons, and very different population sizes, to dispute this), and say that the British implemented Muhammad Ali’s reforms at the same time, then MORE, comparing the semi-independent baseline article, Table MENA-III suggests the CDR gradually rose in Egypt (at least up to 1930, when the table ends) during British rule 1860→1900 CDR (29.6-34.6‰) (baseline article, Table MENA-III), against Dyson’s CDRs, we get a relative excess mortality in India 1881-1941 of 77m-169m. Or if we consider if Soviet (a much more geographically and population-size comparable region) health interventions (which brought the region’s mortality dwon from the ADT, building on some of the infrastructure from the Tsarist era), and the associated CDR around 20‰ in the 1920s and 1930s (with ups (ie early 1930s famine) and downs), were feasible for India in the same time interval (say 1921-1941), we see a relative excess death toll in India of 96m (against Dyson’s CDR figures). If we speculate these measures were feasible from 1881-1941, we get an excess death toll of 346m. If we consider that the USSR brought the CDR down to around 10‰ (or less) by the 1940s and 1950s NOTE The CDR in the USSR climbs by the 1960s, to the low 10s‰; this is, as we’ll review, part a result of post-Stalin issues, and the entwined issue of the enormous military budget during the Cold War the picture is certainly more dire. Again, there is much that would complicate these figures (such as the impact of the harsh El Niño 1881-1921), but they suggest the massive shortcomings of the colonial administration.

Satyam (circa WWII): “But why should we care about U.S.S.R.?”

Communist neighbor: “Because it is the country for all poor people in the world.”

Sujatha Gidla (2017) "Ants Among Elephants", Prelude

These insights greatly foreshadow the developments of 40 A.P. (After Penicillin). It is easy - and to an extent, correct - to argue human wellbeing in the past 80 years has been improved by scientific-technical achievements, such as antibiotics and genetically-modified crops. Clearly I hew to this, as I’ve demarked time periods with it. Yet, as we will see, public action is fundamental to successfully improving public wellbeing, the comparison of India and China the most striking example (and suggestive that the Soviet comparison is qualitatively reasonable).

Overall, this is essential context to understand the achievement of postcolonial states around the world, and especially Marxist-Leninist states, in the 20th century. Certainly, there were major human catastrophes. Yet these are often luridly exploited for polemical purposes to lambast the "failures" of Third World governments - and particular, "communism" - without recognizing (A) the significant achievements in human wellbeing by these states, and (B) the horrific toll that capitalist-oriented administration exacted around the world. As Stephen Wheatcroft puts it, defending his quantitative analysis of the early USSR against detractors:

Such people claim that some events are so important that they should be outside the area of historical study. They claim that we can write poetry about these events, but that we should not dare to apply objective historical analysis. Let me state quite clearly that I reject this as obscurantism. I believe that it is one of the main tasks of the historian to reduce the area of the unthinkable. I make absolutely no excuses for this. I am trying to see the exceptional Soviet experience in some form of historical and comparative perspective. This is not to diminish its exceptional nature, but to return it to the realm of academic thought.

Stephen Wheatcroft (1999), "Toward an Objective Evaluation of the Complexities of Soviet Social Reality under Stalin"

Since then, Wheatcroft has become essential academic reading for the early Soviet experience (not to say he was irrelevant before this point; he wasn’t). Specifically, he was interested in "complex situation in which secular improvements in welfare and mortality are accompanied by massive short-term crises in welfare and mortality", a situation exemplified, perhaps uniquely (although early 20th century Mexico is also perhaps an example), by the early USSR, as well as Maoist China.

What’s so interesting about this period is MORE. Again, to quote Wheatcroft:

I am interested in exploring the period from 1880 to 1955 precisely because it is in this period before modern medicine and urban sanitation could be expected to have been so important when the Soviet population experienced massive short-term demographic crises accompanied by secular improvements.

Overall, the picture suggests that European colonialism neither introduced a sustained negative impact on demography (outside of the Americas) - although its introduction often opened with such sustained crises (ie Africa 1880-1920), and could oversee such (ie India 1880-1920), nor a significant improvement. Life before colonialism was neither idyllic, nor a Malthusian hell. But life could be improved - even in our "before penicillin" age - with policy that actively supported popular welfare. What is notable about European colonial rule - in comparison to local polities, Muslim sultanates, and steppe-people empires - is its self-conscious justification in improving conditions through Western rationality and markets. In this mission, it was a disappointment.

NOTE: I draw lines between datapoints to help plot readability; this doesn’t mean that the trends between datapoints were, in fact, linear, especially for lines between dots over long time periods (ie 1800 → 1850), where likely ups and downs occurred in between (especially the case for Karabchuk 2017 Russia data between 1915→1924)Horizontal lines are every 5 marks on the CDR range; vertical lines every 10 years; the "rough agrarianate CDR range" (orange band) is from 33.5-42‰

Around the interwar period (between WWI and WWII, the 1920s and 1930s), there was a trend in the colonial world of rising population growth rates. While some work has suggested this growth may be over-estimated, that growth occurred is largely consensus. The question then is, is this due to declining death rates, or to rising birth rates?

There are obvious political ramifications here - if death rates declined (putatively to the mid/low 30s ‰), it suggests that there was a meaningful benefit of colonial rule. If instead birth rates increased, this would imply, by contrast, that the colonial regime (and more broadly, capitalist requirements) eroded the agency of women. As far as the data we have suggests, birth rates stayed constant in this period. So was colonial rule good?

There’s another possibility, however: that growth rates in the late 19th and early 20th century were depressed, due to rising mortality rates, and the 1920s and 1930s saw a return to the baseline. In my baseline investigations, we found that, in general, pre-colonial mortality rates around the world hovered in the mid to high 30s‰, with some variation. In the case of Africa, this was confounded by the drastic demographic and political impacts of the slave trade, but seems plausible that the "natural" demographic trends were along this line as well.

Therefore, much of the putative mortality decline is explainable via a return to baseline mortality rates - although public health interventions in the interwar period certainly had some positive impact. That said, the mortality rates were declining... from mortality peaks in the 1880s-1920 consequent of colonial intervention. While scholars caution that the debate of rising fertility vs declining mortality is not settled, declining mortality doesn’t necessarily reflect beneficent colonial administration.

MORE

Contagionism vs Miasma → Germ Theory

Colonial Rule + Germ Theory → Tropical Medicine (a la Patrick Manson)

Colonial Rule imperatives → poor investment in colonial medicine → mortality crisis

→ have to worry about public health as an economic concern